From Downtown to East Hills to the Westside, a sea change is well underway in almost every city neighborhood of Grand Rapids. New developments catering to “desirable” (that is, economically valuable) residents are cropping up like an invasive species, generating a great amount of uncritical hype. The process easily fits the definition of gentrification, but many are still struggling to identify the causes and consequences of gentrification locally.

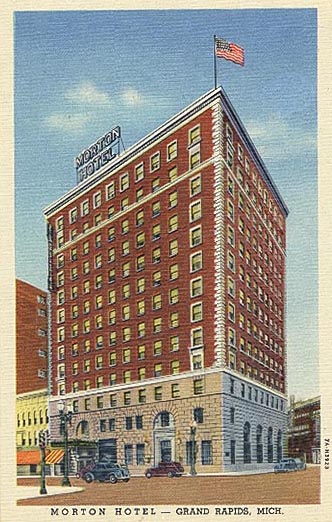

One of the most striking case studies of our understanding of gentrification in Grand Rapids is the Morton House building, standing tall at Ionia Avenue and Monroe Center in the middle of downtown, and currently swathed in the colorful banners of Rockford Construction Company. Originally built as a luxury hotel almost a century ago, the building was acquired in 1971 by Saperstein Associates Corp., a property management company based near Detroit, which operated the Morton House as a multi-family Section 8-based housing project under a 40-year contract with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Projects like this can offer stable housing to people who have trouble finding and affording it elsewhere for a variety of intersecting reasons – mostly people who work low-wage jobs, are disabled, or who have struggled with mental health or addiction. Like most low-income (low-priority) housing projects, it fell into disrepair over the years, with reports of heating and other maintenance issues and bed bug infestations. When their HUD contract expired in 2011, Saperstein Associates Corp. said they felt the building had “completed its life-cycle as a multi-family, independent affordable housing” location, opted out of the Section 8 program, and put the building up for sale.

Before the building had even hit the market, the roughly 200 residents were given a three-month deadline to move out. A coalition of non-profits and social services helped coordinate the daunting relocation process: the Grand Rapids Housing Commission put on a housing fair and greatly expanded their Section 8 Program vouchers so that residents could qualify for Section 8 housing elsewhere, the Department of Human Services funded more than 128 security deposits with state emergency relief funds, and local non-profits like Servant’s Center and Dégagé Ministries helped many residents cover some moving costs. The Housing Commission’s 2011 annual report states the obvious, that “relocating the residents of Morton House posed significant challenges since many households faced extraordinary financial and logistical hurdles.”

Before the building had even hit the market, the roughly 200 residents were given a three-month deadline to move out. A coalition of non-profits and social services helped coordinate the daunting relocation process: the Grand Rapids Housing Commission put on a housing fair and greatly expanded their Section 8 Program vouchers so that residents could qualify for Section 8 housing elsewhere, the Department of Human Services funded more than 128 security deposits with state emergency relief funds, and local non-profits like Servant’s Center and Dégagé Ministries helped many residents cover some moving costs. The Housing Commission’s 2011 annual report states the obvious, that “relocating the residents of Morton House posed significant challenges since many households faced extraordinary financial and logistical hurdles.”

Obviously, the previous low-income housing project was not a solution for the poverty that its residents experienced, merely a measure that helped keep a roof over their heads while they navigated it. And while many residents were understandably upset about being uprooted from their stable home of many years and suddenly forced into a cut-throat rental market, some were able to use the change as an opportunity to find homes that offered more space and fewer bed bugs. Still, those who would justify the displacement of poor downtown residents by pointing out the poor conditions in which they were living are missing the point entirely.

After the building was emptied of its previous residents, the property was bought by Rockford Development and RDV Corp., an investment and holdings company owned by the DeVos family. Then after the acquisition, the building sat empty for about three years. It was only last fall that extensive renovations began and that the new use for ‘the Morton’ was announced: an upscale, market-rate apartment building with retail space on the ground level. The buffer of time between the evictions and the unveiling of the new plan conveniently diffused any critical discussion of the changing use. Indeed, most people seem to have forgotten what the building once was – and some of the media celebration of the new development was able to assert that the project would create new housing in a previously vacant building.

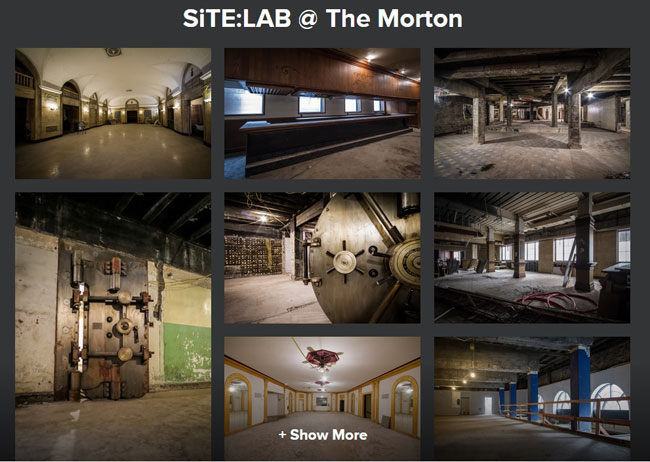

The building was also chosen as the 2014 venue for SiTE:LAB, an arts organization that fills “underutilized” spaces with site-specific art installations. The installation opened as a part of ArtPrize, the (in)famous public art competition that turns downtown Grand Rapids into a spectacle for suburbanites and well-heeled out-of-towners, and Rockford Construction took advantage of the crowds by opening a model apartment for visitors to walk through on their way to or from the exhibitions. The event created a sense of excited potential for the space, while avoiding any deeper exploration of the forces that were shaping it. Most of SiTE:LAB’s promotion referred to the Morton building as abandoned without ever answering the question “abandoned by whom?”

The investments in renovating the building easily dwarf the amount of money that went into the resident relocation project in 2011. The $34 million renovation is being funded in part by a $4.3 million low-interest loan from the Michigan Strategic Fund and $2 million in tax incentives approved by Grand Rapids’ Downtown Development Authority.

According to mLive, “rental rates for the 60 one-bedroom units will begin at $1,300 a month and go up, depending on the view. The 30 two-bedroom units, each with two bathrooms, will begin at $1,600 a month, while 10 studio apartments will begin at $1,000 a month.” There will also be condominiums on the upper floors that will likely cost much more, and quite a bit of retail space on the ground level.

If the rental prices don’t make it obvious enough, the language and photos used to advertise the Morton – showcasing expensive modern coffee tables stacked with heavy art books and wine glasses ready to sip – make it clear that the building is intended for “sophisticated”, luxury-seeking residents. This shift in housing priorities is not a coincidence of market opportunity, but part of a calculated long-term plan that is turning downtown and near-downtown neighborhoods into playgrounds for those with money to spend.

City Economic Development Director Kara Wood has said that “the Morton project will ‘catalyze’ downtown development and help the city achieve its goal of doubling the number of downtown residents.” Kent Companies, the construction company contracted to re-do the building’s floors, boasts that “the Morton House is in prime position to draw residents back to the city’s urban core.” And Kurt Hassberger, the President of Rockford Construction, remarked to the media that “we want to create a place where our kids want to stay, and live and work” – a friendly sound bite that has a subtle callousness to it (whose kids? And why do they deserve a nice place to stay more than the people who were there first?)

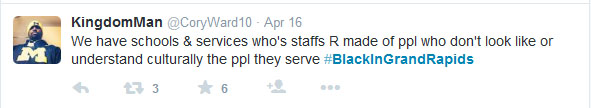

The inner city is no longer for the impoverished, it’s for well-off professionals who want to be “at the center of it all.” While we’re all familiar with the problems that tend to plague inner-city areas with concentrated poverty, the shift does not actually address systemic causes of poverty – it merely displaces and disperses its effects.

But where is it being displaced to? The reporting on the relocation of the Morton House residents doesn’t quite answer this question, merely saying that all residents were relocated on schedule and calling that a success, but from broader housing trends we can infer that many residents probably had to move to areas further from the center of the city, where transportation and social services can be harder to access. And the moves were also likely to disrupt supportive social relationships that may have developed over years of living in the same place, further fueling the isolation and instability that characterize life in poverty.

While concentrated poverty – the concentration of low-income households in the same neighborhoods – is still highest in cities, it’s growing at the fastest rate in suburban areas. And of metro areas where the number of poor people living in “concentrated poverty” neighborhoods is increasing, Grand Rapids has scored one of the highest rates of increase since 2000. Since suburban communities were created for middle-class families and are ill-equipped to support low-income populations, there’s a good chance that entirely new islands of concentrated poverty are being created by this process.

As we’ve discussed before (and will discuss more in the future), long-time residents don’t necessarily need to be kicked out by developers of new property or business in order for the changes brought by development to displace them over the long term. But even when people are directly and immediately displaced, this fact is usually either ignored or quickly excused and the focus redirected towards the “positive” economic effects of the development.

This process is in no way unique to the Morton building or to Grand Rapids. It’s a small iteration of a grander process affecting all cities, and reflective of how our economy perpetuates the hierarchies that it was built on. You can hear echoes of the same story in this video concerning over 100 seniors who were evicted from the Griswold House, a low-income senior living facility in Detroit which was then redeveloped into luxury housing. The videographer makes a stirring remark in the video description: “It’s not enough to just notice one group of people prospering and another dying.” Just telling the story of the Griswold House or the Morton House is not enough to keep the same story from recurring over and over again – but in a city where stories like this are either utterly ignored or warped into publicity campaigns for developers, hopefully it’s a start.