New phrases are invented every year to overshadow the word “gentrification.” A few decades ago it was just “revitalization” or “urban renewal,” while in recent times new terms have cropped up such as “inclusive growth,” “development without displacement,” and a new favorite of Grand Rapids: “place making.” Marketing and branding schemes don’t come from nowhere, they are meant to hide and shift public dialogue into a direction favorable to economic power. This is nothing new. The myth of a post-racial society has permeated the United States for decades, with code words such as “thug” and “welfare queen” concealing the racism at the foundation of this society. The word “gentrification” must be hidden because it characterizes the social, economic, and political orientation of development as inherently racist.

An economic process by any other name…

Grand Rapids has been ranked the 2nd worst out of 52 urban centers for economic opportunities for black people in the entire country according to a recent Forbes Magazine article. Nearly 45% of black residents in Grand Rapids live in poverty. Grand Rapids-Wyoming is the 26th most segregated metropolitan area between white and black people in the United States. Black people on average give the city a worse rating than white people. The GRPD regularly stop, photograph, and fingerprint black men who are not being charged with any crime and as a result the department is currently facing a lawsuit.

Meanwhile, the city is receiving accolades for its economic growth. Lonely Planet named Grand Rapids as the top US travel destination of 2014, the same year it was ranked 5th among U.S. cities benefiting most from economic recovery. In 2013, Grand Rapids won the “Beer City USA” award for its numerous microbreweries and bars. These awards cater primarily to white people – the culture of entrepreneurship so praised in Grand Rapids rarely celebrates black businesses. The cultural activities celebrated are also a celebration of white pseudo-culture – i.e. stuff white people like.

Marginalization in every sense of the word describes the process applied to many of Grand Rapids’s black residents. Not only are the majority of non-white people held back from economic opportunities, but for white people these problems and others are kept out of sight and out of mind. For a city the size of Grand Rapids, that means that these social inequalities affecting majority black areas are happening literally a block or two away from majority white areas, and yet remain largely unseen.

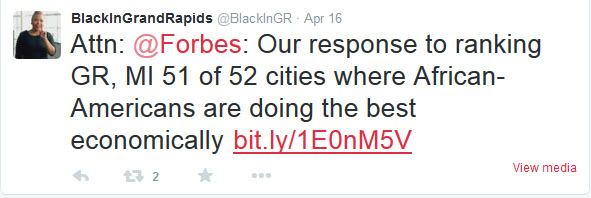

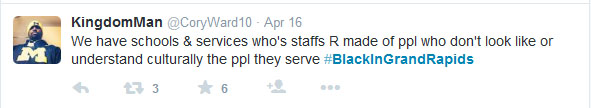

White Grand Rapids exhibits a combination of callous, oblivious, and indifferent attitudes towards the marginalization of the city’s black residents. Downtown Grand Rapids Inc. and the Grand Rapids Community Foundation sponsor a “Place Matters” feature on the local news website The Rapidian, which strives to make the city look more appealing to potential professional newcomers. Grand Rapids has been participating in a global trend where cities compete with each other to attract entrepreneurs and a certain class of new residents. This process crafts a regional identity into a kind of brand, and exploits peoples’ sense of belonging into a kind of brand loyalty. Seriously examining the racial and economic disparities in the city doesn’t make for flashy PR. A public relations group responded to the aforementioned Forbes Magazine article with a #BlackInGrandRapids campaign on Twitter as well as showcasing a video, both of which were meant to counter a narrative which brought bad press to Grand Rapids.

This move failed, as people quickly used the hashtag to post statistics and stories about the oppression and marginalization of black people in Grand Rapids.

Gentrification unearths an ugly truth about race in Grand Rapids and the United States: that blackness is considered undesirable, dirty, and dangerous while whiteness is seen as pure and safe. It is a centuries old narrative whose parts are updated every generation – but it’s still largely true. White people refer to areas with mostly black people as “ghetto,” even if the residents are middle class. The Meijer on Kalamazoo and 28th is colloquially called the “ghetto Meijer.” Living south of Franklin is in “the hood.” While tolerant multicultural society urges white kindness to a black neighbor or co-worker, it does so under the implication that white people form the majority and hold the power. This is why “development without displacement” is a joke, and those who urge for it are either naive or have ulterior motives. On the flip side of this, some white people are aware of the sterility of whiteness, and subsequently desire to be around people of color, fetishizing areas with majority black and brown people as exotic and “authentic.” These white people tend to unknowingly be the vanguard of gentrification, making space where more white people feel comfortable inhabiting.

The Vacancy is Too Damn Low!

As pointed out in our “Fulton Place & Development” article,

“Gentrification scholars have long recognized that ‘displacement’ doesn’t exclusively mean physical displacement and that displacement can happen over time as the culture and composition of the neighborhood changes. Gentrification is a concept that captures the ways in which most ‘redevelopment’ projects involve a shift from one class to the other, regardless of whether or not they involve direct displacement.”

This process is aided due to a large influx of new residents into the city. While gentrification is normally seen as a raising of rent, in this case that might not even be necessary. Grand Rapids has the lowest rental vacancy rate in the country at 1.6% compared to the national average of 7%. New residents pulled in by the allure of urban living likely benefit from race and class privileges over long-term residents, which might include clean arrest records, high credit ratings, stable incomes, and even white-sounding names. In securing loans, applying for housing, finding employment, and in almost every other dimension of public life they have the advantage.

The Wealthy Street Model

On most nights along Wealthy Street, there are large crowds of (white) people visiting a host of bars, breweries, and eateries which serve up the latest in foodie trends. From fish tacos and micro-brews to artisan vegan food and $12 macaroni and cheese, they can all be found. During the day, boutique stores, salons, and coffee shops are popular destinations. Visitors come from outside the neighborhood – it has become a destination spot among hip travelers and residents of other neighborhoods alike. Fancy cars line the streets, while expensive bikes take up space on the bike racks. It’s a mix of hipsters, affluent millenials, families, and more – the overwhelming majority of which tend to be white. Walk a few blocks north from the intersection of Wealthy Street and Diamond Avenue, and you are in an even more affluent area where restaurant options rival those found in bigger cities. The money and wealth radiates out from the area, creating a two-block stretch that might make one surprised that they are still in Grand Rapids. On the walk over, one may have noticed the homes, many of which are owner occupied and well-maintained, creating a desirable neighborhood popular with homeowners and renters alike – including the coveted young professionals. However, walking just a block south of Wealthy Street and Diamond Avenue evokes the feeling of being in a totally different world. The quality of homes drops dramatically, the presence of police increases, and numerous indicators of generational poverty and disinvestment are everywhere. And the racial composition of the neighborhood almost flips. While those visiting and owning businesses along or north of Wealthy Street tend to be white, those living south of Wealthy Street tend to be black. The dividing line of Wealthy Street couldn’t be clearer.

The Wealthy Street corridor has been heavily gentrified in recent years. Like many inner-city neighborhoods, there was significant disinvestment in the second half of the 20th century, which accelerated following the 1967 riots against police. In the intervening years, it was largely forgotten about by white residents. The standard picture painted by the neighborhood’s boosters is that prior to their efforts, it was overrun with drug dealers and gang members. While these components certainly existed, it’s worth considering the ways in which this story creates a racialized narrative. This is especially important in light of the fact that the developments along Wealthy Street are very one-sided, directed at – and benefiting – primarily white people. This kind of critical distinction is absent in most discussions of Wealthy Street. If you look at media coverage or listen to neighborhood boosters, you are far more likely to hear stories about the near super-hero like role individuals had in facing down drug dealers, the heroic efforts of homeowners renovating their homes against all odds, the importance of creating a historical district, and the opening of new businesses in helping to “turn” the neighborhood. Unfortunately, many of these protagonists are white and many of the investments come from outside the neighborhood. Black-owned businesses do still exist along Wealthy Street, but it is those that cater to the new class and race of customers that are celebrated in the media.

While there has been some debate over whether or not the neighborhood has undergone gentrification, it tends to be a charged conversation. In it, most popular myths of gentrification are invoked and there is little actual examination of what has changed on Wealthy Street. People will assert publicly that gentrification is not happening and argue that there is no displacement of existing residents. This of course is limited in that it assumes a narrow definition of displacement, focusing only on physical displacement rather than cultural. It’s a different form of displacement that is taking place when black residents may not feel welcome in an area built to cater primarily to white dispositions and cultures. On the topic of displacement, this is a common issue in gentrification studies as the process of measuring displaced residents is difficult as they are by definition gone from the areas where sociologists would go to interview them – thus making the displaced largely untraceable. Yet it’s doubtful that those who clamor of evidence of displacement actually care, as they are often the proponents of the gentrification. There has been relatively little study of Wealthy Street, leaving one to rely primarily on perceptions based on the proliferation of upscale establishments and the experience of walking through the neighborhood and noting what is going on. When it comes to actual studies, one from 2002 found that the area was undergoing a process of gentrification and that was before things really took off in the mid-2000s.

The wholesale transformation of the area is unmistakable. Even as some continue to celebrate it, others have been more critical, arguing that the benefits of the development have not moved south of Wealthy Street and have not been extended to non-white residents. In some cases, it’s mentioned in a very matter-of-fact way that gentrification did happen and that it clearly did not benefit residents. Even proponents of what happened on Wealthy Street have occasionally expressed regret, admitting that the neighborhood lacks middle-income housing. Often, the question of whether or not gentrification happened along Wealthy Street falls along racial and class lines, with those who benefit from gentrification being the staunchest and loudest in their opinions that it did not.

Wealthy Is Everywhere

Despite the negatives associated with the gentrification of Wealthy Street, many in the city – especially in the development community and its cheerleaders – see it as a sort of “model” of how “revitalization” can happen in Grand Rapids and what the desired end goal is. Bear Manor Properties – which at the time owned Electric Cheetah, Brick Road Pizza, and the Meanwhile Bar – asserted, “We feel like Wealthy Street is a model for the future of good development in the city.” In regard to recent developments on the Westside, developers have not been shy about invoking the image of Wealthy Street when discussing the neighborhood’s future. The owners of the forthcoming Harmony Hall – a second location for Harmony Brewing – have said that “…it reminds me a lot of working on Wealthy Street back in 2006 and 2007.” Others have said that the Westside will be “like Eastown” in 5-10 years. And it’s a theme that is consistently invoked in the media. Developers and their boosters – in the media and gentrifiers – speak of how Bridge Street is shaping up to be a “destination” neighborhood.

In the way that criticism of the gentrification of Wealthy Street is shot down with the assertion that before it was overrun with drug dealers and gang members, gentrifers on the Westside speak of the need to eliminate “low use” and an undesirable “culture” (in reference to a lingerie/video store and an adult theater) that existed along Bridge Street. Without defending the previous businesses, it should be obvious that it does not have to be an either/or scenario, as if the choice must be between abandoned buildings and gentrification. Along with the rhetoric, the constellation of restaurants and developments planned for on the Westside point towards a future like Wealthy Street with upscale clothing stores, restaurants, and breweries planned for the neighborhood. Along with these, a number of housing developments have been proposed for the area which introduce rental rates far outside the norm for the area. Ultimately, the original cultures will be replaced – witness the number of restaurants planning to serve Polish and Mexican fusion cuisine – as an insulting homage to those who have been (or will soon be) displaced. Meanwhile, people living in the adjacent neighborhoods will be increasingly unwelcome and their opinions will be deemed less and less relevant. Invoking Wealthy Street as a model may be accurate in terms of conceptualizing what Bridge Street will look like and who it will cater to, with the new build gentrification, it may be an even more totalizing transformation.

The “Wealthy Street Model” of gentrification is moving beyond Bridge Street. New projects in other areas of the town are repeating a similar pattern. One developer commits to an area, only to have a number of other projects follow in their footsteps. This is happening in the Creston neighborhood, where Derek Coppess of 616 Development says that “you’re going to see a whole different neighborhood.” While 616 Development is building new developments, they are also promising the same kind of total transformation that happened on Wealthy Street. He even goes so far as to describe the neighborhood – home to many people and businesses already – as being made of “great bones” in “… need [of] an infusion of market-rate people who are here 24-7.” News reporters couldn’t be happier, barely able to contain themselves at the prospect of yet another brewery opening. As a new class of people is introduced to the neighborhood, a feeling of dislocation and exclusion is inevitable and a variety of direct and indirect pressures will begin to bear down on those living on the edges of the gentrifying blocks.

The opening of Hall Street Bakery on the corner of Fuller and Hall should be considered as another iteration of the “Wealthy Street Model” of gentrification. Hall Street Bakery—operated by the same owners of the Wealthy Street Bakery—consciously identifies with and celebrates the role that Wealthy Street Bakery had in the gentrification of Wealthy Street. David LaGrand, one of the owners of the two businesses, said in an interview with MLive, “The bakery really helped kick off some development on Wealthy Street years ago and we’re hoping this will stimulate some investments in the (new) neighborhood.” He has also said that “The neighborhood in Hall and Fuller looks a lot like what Wealthy Street looked like when we (first) invested there.” It’s worth noting that while he celebrates the “revival” of Wealthy Street, LaGrand does not believe gentrification actually happens in Grand Rapids. With the Hall Street Bakery opening, one can’t help but wonder if the same demographic shift – both in terms of race and class – that occurred along Wealthy Street will happen around the Hall Street Bakery. After all, gentrification scholars such as Neil Smith have long recognized the importance of “outpost” businesses in the process of gentrification that test the waters for future development.

“Best Side” for long?

The near Westside of the city just across the river was noted as one of Grand Rapid’s “most integrated” areas according to a MLive article citing US Census data. The population has historically been composed of working class black, white, and latin@ people. Of course, that is not to say that the area is racially harmonious, but just to note that at the present time, it is relatively diverse – especially by Grand Rapids standards. It’s no secret that urban planners as well as construction and real estate firms are in the process of gentrifying Bridge Street and the Westside in general, all with city commission approval. As expected, the microbreweries, boutique clothing stores, and market-rate housing are clearly not meant for long-term residents. West Grand Neighborhood per capita income is an average of $14,880.26 a year, John Ball Park Neighborhood’s is at $20,415.62. In contrast, a pair of pants at Bridge Street clothing store Denym costs $100-200. Rent at the 600 Douglas project is market-rate, which ends up being $975-2,100 a month.

At the same time, landlords are buying up newly vacant family homes near Lake Michigan Drive, many of which have recently been foreclosed on, and are renting them to GVSU students, a demographic that is 84% white. A house, for which a family may once have paid a mortgage of less than $1000 a month, is rented to four students at $400 each. In addition to becoming less affordable, the neighborhood changes in character. The party lifestyles of privileged youth directly clash with neighboring families or older residents. Even if not priced out, long-term residents might just get sick of hearing that same Jay-Z song ritually blasted at 2 AM every night.

Whether it’s predatory landlords renting to boisterous students or capitalists and city planners trying to attract more capital along Bridge Street, the limited gains of racial co-existence made on the Westside will likely be gone in the near future. But why should officials in Grand Rapids care? They already rank 51 out of 52 cities in economic opportunities for black people. They can hardly go any lower, and city officials have made it quite clear that gentrification is the official policy, regardless of its consequences.

“No Neutrals There”

In 1931, the United Mine Workers of Harlan, Kentucky battled an openly violent conflict against the mine’s owners. Florence Reece, whose husband was one of the miners, wrote the song “Which Side Are You On?” to implore that there can be “no neutrals” amidst such conflict. The mine owners and the structural forces behind gentrification share the ability to create and change the world around those that inhabit it. To take a passive or neutral stance in either situation is ultimately to side with the oppressor.

On October 6, 2014 a group of activists disrupted the St. Louis Opera, standing up from their seats and singing an altered version of “Which Side Are You On?” called “A Requiem for Mike Brown.” The last year of revolts over police killings has shattered the mask of a post-racial society for all who are willing to look. Gone are the days when one could sincerely pose the question in mixed company of whether racism still exists in this country. In this time of gentrifying displacement, cold-blooded murder of black people by a white supremacist, and ongoing revolt against the violence of the police, more so every day the question shifts from whether racism exists to a choice: “which side am I on?”