In debates around gentrification, the issue of displacement is often brought up. It’s a core component of definitions of gentrification, with most agreeing that displacement is a consequence of gentrification. However, within the academic world, there is a lot of debate about what exactly “displacement” means and how it should be defined. It’s something that needs to be considered, as how we conceptualize displacement is essential to understanding gentrification.

First, it is important to understand that “the displaced” aren’t an abstraction. They are real people and they have lives that matter. Similarly, displacement is a real threat. Caitlin Cahill captured this well writing:

“The pressure of displacement is not an abstract threat but experienced in material ways: slips under the door offering a buy out in public housing, family members relocating temporarily never to return home, personal experiences of being harassed by landlords, doubling up of families in tiny apartments, and seeing friends displaced. Narratives of deceit, betrayal and loss characterize the ‘war stories’ of displacement, offering an inside perspective on the social costs of gentrification (Alicea 2001: Muniz 1998).” [1]

As it stands, the relationship between gentrification and displacement is complicated. Proponents of gentrification often cling to the idea that if there isn’t immediate and verifiable evidence of displacement, then there is not gentrification. For example, if a development is built on a vacant piece of land—perhaps including market-rate apartments and a ground-floor brewery—many won’t consider it gentrification because they argue that nobody was living on that piece of land, and nobody was forced out. The lack of evidence for direct and immediate displacement is often used as a way to silence critics and dismiss discussions about gentrification.

However, the focus on physical displacement is in many ways exceedingly narrow and ignores the complexity of how people are displaced due to gentrification. That said, people are certainly directly displaced by gentrification. This has occurred in Grand Rapids, witness the demolition of homes on the Westside, the sale of homes in the Belknap neighborhood, and the recent proposal to demolish a block of homes for apartments along Michigan Street. Physical displacement is a consequence of gentrification, and it happens regularly as buildings are bought and sold once developers and individual homeowners move into a working-class areas and start spending large amounts of cash to acquire land and buildings.

Tracking Displacement

Measuring displacement is difficult. While one can count the number of houses demolished, developing more complex accounting methods is often difficult. For example, if the homes being demolished were owned by landlords—as is often the case in low-income neighborhoods—it’s easy to talk about “willing sellers” and to minimize the displacement as leases are quietly allowed to expire at the end of their term. In the case of neighborhood level change, academics have long discussed the difficulty of measuring displacement due to gentrification:

“…it is nearly impossible for independent researchers to design small, targeted studies of displacement effects in gentrifying neighborhoods: poor and working-class people displaced by gentrification have disappeared from precisely those places where researchers go to look for them. Accurate measurements of displacement are impossible with after-the-fact surveys conducted in the origins of displacement; instead, the researcher must find households in the destinations where people are forced to move. Since those displaced from a single gentrifying neighborhood may wind up in a wide variety of places – nearby poor neighborhoods, more distant low-cost suburbs, or even distant cities or regions – the only definitive way to measure gentrification-induced displacement is to track down individual households who have moved out of neighborhoods over time as gentrification proceeds, and to ask them detailed questions about their reasons for moving. This is extremely expensive and time-consuming.” [2]

Put simply, tracking displaced people is largely an impossibility because they are gone from the places where one would look for them. Those affected by gentrification tend to be poor, which makes tracking them all the more difficult. Surveys and studies that focus on “households” miss those who move in with friends and family, while the fact that many people frequently move in and out of neighborhoods for any number of different reasons further complicates the matter. [3]

Other academics studying gentrification have pointed out that there is often “a substantial time lag between when the subordinate class group gives way to more affluent users” [4]. Displacement isn’t always immediate, leading some researchers to argue that what is key is that it involves the construction of space and the creation of an environment hostile to existing residents. Kathe Newman and Elvin K. Wyly argued that we shouldn’t “… consider residential displacement as a litmus test for gentrification” and that we should consider “…the impact of the restructuring of urban space on the ability of low-income residents to move into neighbourhoods that once provided ample supplies of affordable living arrangements.” [5]

Social and Cultural Displacement

In academic discussions of displacement, there is a lot of debate around how gentrification displaces people culturally and/or socially. The idea of “social displacement” as a key aspect of gentrification was articulated by Michael Chernoff who described it as:

“…the replacement of one group by another, in some relatively bounded geographic area, in terms of prestige and power. This includes the ability to affect decisions and policies in the area, to set goals and priorities, and to be recognized by outsiders as the legitimate spokesmen for the area.” [6]

This works in many different ways:

For example, the loss of political control in an area can lead to demoralization, or a sense of one’s lifestyle being threatened. At some point, residents or businesses may feel compelled to leave the area; thus physical displacement may stem from social rather than economic pressure. Social displacement might be marked by a gradual withdrawal from neighborhood activities of the displaced. They drop out of local organizations or remove themselves from political activities. Thus, they complete their own displacement by relinquishing attachments to the associations which were formerly the bases of their power.” [7]

“Cultural displacement” is another important aspect of the displacement debate. It concerns the effect that gentrification has on those who are able to stay in a gentrifying neighborhood. What does it mean to live in a neighborhood that is being transformed by outside forces?

“The neighborhood context is being taken over and changed beyond recognition. Displacement is experienced in this regard as a process of effacement at the neighborhood scale, where the signs personal and cultural heritages are erased. What does it mean when the salon where one’s mother had her hair done every two weeks closes down?

…

In short, gentrification is experienced as a loss of self, community and culture. The threat of erasing of ‘my grandmother’s house,’ ‘my history’, and ‘my neighborhood’ is accompanied by feelings of anxiety and anger. ‘I don’t belong here’: this anger expresses a sense of not feeling welcome in one’s own community.” [8]

This creates an environment where existing residents beyond those immediately displaced, feel an acute “pressure of displacement”:

“…displacement affects many more than those actually displaced at any given moment. When a family sees its neighborhood changing dramatically, when all their friends are leaving, when stores are going out of business and new stores for other clientele are taking their places (or none at all are replacing them), when changes in public facilities, transportation patterns, support services, are all clearly making the area less and less livable, then the pressure of displacement is already severe, and its actuality only a matter of time… We thus speak of the ‘pressure of displacement’ as affecting households beyond those actually currently displaced.” [9]

If we’re going to be honest, we must acknowledge that displacement due to gentrification and development has happened in Grand Rapids, it is happening, and it is going to happen in the future. There is no way around it. It’s more a question of what type of displacement—physical or cultural—is happening. And of course, the even more difficult question, what can be done about it?

Sources

1. Caitlin Cahill, “Negotiating Grit and Glamour: Young Women of Color and the Gentrification of the Lower East Side,” from >City & Society (2007), in Loretta Lees, Tom Slater and Elvin Wyly, eds., The Gentrification Reader, (London: Routledge, 2008), 305.

2. “Introduction to Part Four,” The Gentrification Reader, 319.

3. “Introduction to Part Four,” 318-319.

4. Tom Slater,“The Eviction of Critical Perspectives from Gentrification Research” from >International Journal of Urban and Regional Research (2006), in The Gentrification Reader, 578.

5. Kathe Newman and Elvin K. Wyly, “The Right to Stay Put, Revisited: Gentrification and Resistance to Displacement in New York City” from Urban Studies (2006), in The Gentrification Reader, 544.

6. Michael Chernoff, “Social Displacement in a Renovating Neighborhood’s Commercial District: Atlanta”, in Japonica Brown-Saracino, ed., The Gentrification Debates, (New York: Routledge, 2010), 295.

7. Ibid., 295.

8. Cahill, 307.

9. Peter Marcuse, “Abandonment, Gentrification, and Displacement: The Linkages in New York City” from Gentrification of the City (1986), in The Gentrification Reader, 335.

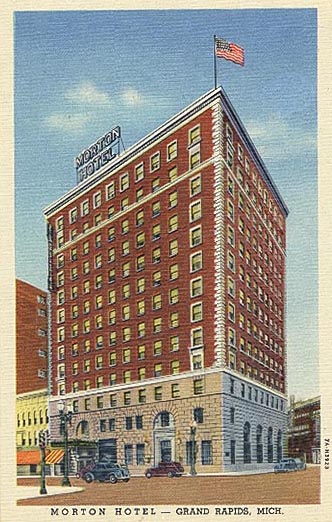

Before the building had even hit the market, the roughly 200 residents were given a three-month deadline to move out. A coalition of non-profits and social services helped coordinate the daunting relocation process: the Grand Rapids Housing Commission put on a housing fair and greatly expanded their Section 8 Program vouchers so that residents could qualify for Section 8 housing elsewhere, the Department of Human Services funded more than 128 security deposits with state emergency relief funds, and local non-profits like Servant’s Center and Dégagé Ministries helped many residents cover some moving costs. The Housing Commission’s 2011 annual report states the obvious, that “

Before the building had even hit the market, the roughly 200 residents were given a three-month deadline to move out. A coalition of non-profits and social services helped coordinate the daunting relocation process: the Grand Rapids Housing Commission put on a housing fair and greatly expanded their Section 8 Program vouchers so that residents could qualify for Section 8 housing elsewhere, the Department of Human Services funded more than 128 security deposits with state emergency relief funds, and local non-profits like Servant’s Center and Dégagé Ministries helped many residents cover some moving costs. The Housing Commission’s 2011 annual report states the obvious, that “