Like many major urban streets in the US, Division Avenue of Grand Rapids, Michigan has a varied history as a home to hotels, stores, restaurants, and other businesses. It was a vibrant neighborhood at numerous points in the city’s history. However, with the so-called “race riots” in Grand Rapids of 1967, white flight, and urban renewal, Division Avenue became a different place. It was home to low-income residents, homeless populations, and abandoned and dilapidated buildings. In response to the general flight from this area, various social service agencies, ministries, and shelters opened along the street. The area was, and to some extent still is, one of the densest and poorest neighborhoods in Grand Rapids. South Division in particular was ignored in the 1990s as developments took place in other areas of downtown.

For years the street seemed resistant to gentrification. Numerous art spaces and music venues—from The Basement to The Reptile House—were home to vibrant alternative and underground scenes, yet Division remained a place where many feared to go. Despite the best efforts of various investors, city boosters, and city government—the street retained its image and patterns. In the mid-2000s with the “Cool Cities” initiative and the Avenue for the Arts designation, The Grand Rapids Press even described the street as undergoing “fitful gentrification,” but the process remained slow.

This began to change in 2012 and 2013, when many new projects were undertaken. As interest in downtown living increased and developers began to make significant profits off market-rate rentals, investors and city planners began to look at South Division anew. The Harris Building, once a home to the non-profit charity In The Image, was developed into an event space with an upscale (seriously, a bag of noodles costs $12) artisan pasta shop on the ground floor. The DAAC, an almost ten year old art and performance venue, lost its space due to rising rent. Along with this, a number of new boutique stores, restaurants, and housing developments opened, both on Division and in the surrounding blocks.

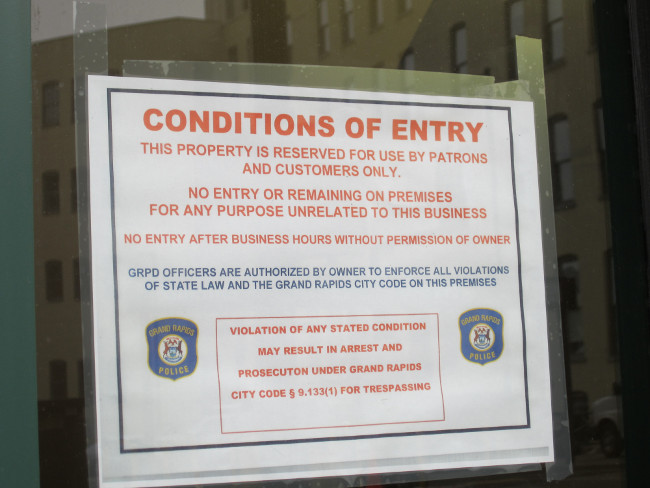

Still, South Division remained an area shaped by its legacy as a haven for low income and homeless populations. Many social service agencies remain located on the street and homeless people still slept in doorways and congregated along the streets. Various types of crime—theft, vandalism, drugs—took place on a regular basis. In 2012, many of these problems were identified as an obstacle to the economic development of South Division between Fulton and Wealthy. The Division Avenue Task Force specifically sought to “identify solutions” to panhandling, loitering, graffiti, and the so-called “public nuisances” that take place on the street. It was clear that if South Division was to change, it would have to be “cleaned up.” Ultimately, this is a new form of colonization—where areas previously unsafe for capital must be tamed, pacified, and cleared of obstacles, just as the very land on which we now live was stolen from the Anishnabek people.

Ambassadors To Whom?

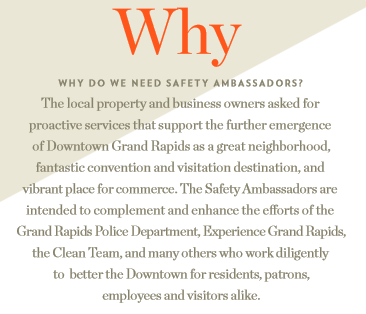

The solution the Division Avenue Task Force recommended was to implement national urban services company Block By Block’s Safety Ambassadors Program; not just on Division, but for all of Downtown. The “problems” on Division are a Downtown-wide phenomenon, especially as the boundaries of “Downtown” expand into working-class areas adjacent to it. The last ten years of urban development have been characterized as a reinvigoration of wealthier people’s interest in living in the city, often at the expense of the urban poor and working class who end up being crowded out by subsequent rising costs of living. This process has been an inversion of the suburbanization that characterized post-WWII development. This demographic shift has been fueling the process of gentrification in modern cities—including Grand Rapids. The Downtown Ambassadors, operating as both low-level security and customer service for downtown, aid in facilitating this gentrification.

The Downtown Ambassadors perform what are essentially low-conflict policing and sanitation efforts as well “customer service” in order to make a new, wealthier population in downtown feel welcome.

The Downtown Ambassadors are paid employees who patrol downtown in teal uniforms with pockets full of brochures, often while riding segways. They perform what are essentially low-conflict policing and sanitation efforts as well “customer service” in order to make a new, wealthier population in downtown feel welcome. The “customer service” role works for both current residents who only recently have felt safe venturing downtown and tourists wandering aimlessly during events such as ArtPrize and other festivals. For these types, the Ambassadors are available to give directions to the lost and provide umbrella escorts if it’s raining.

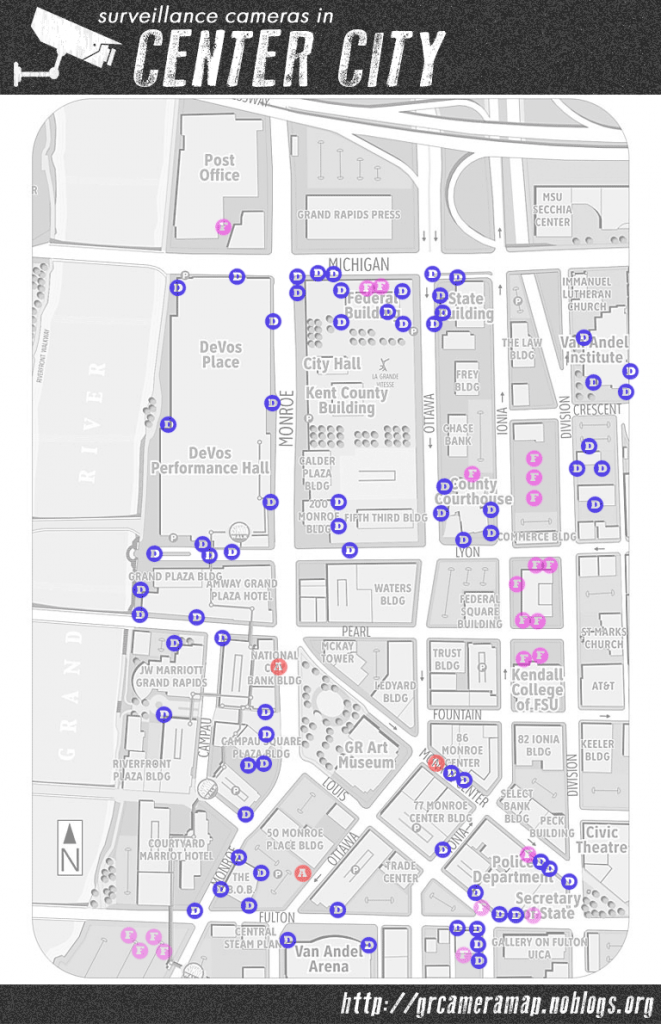

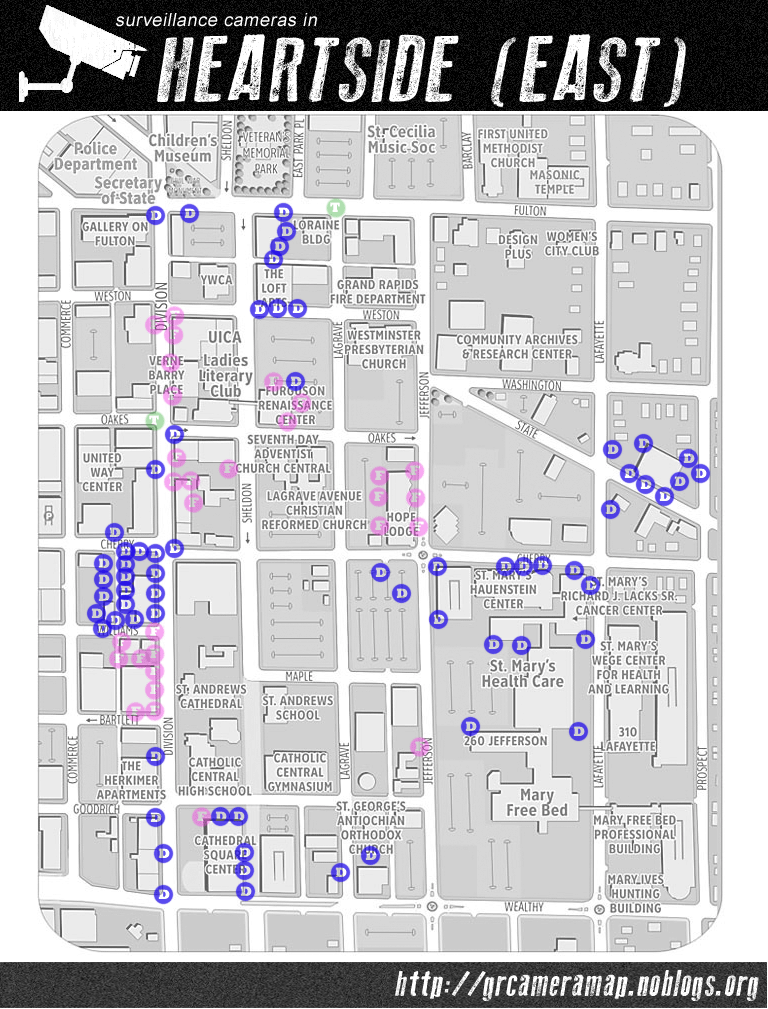

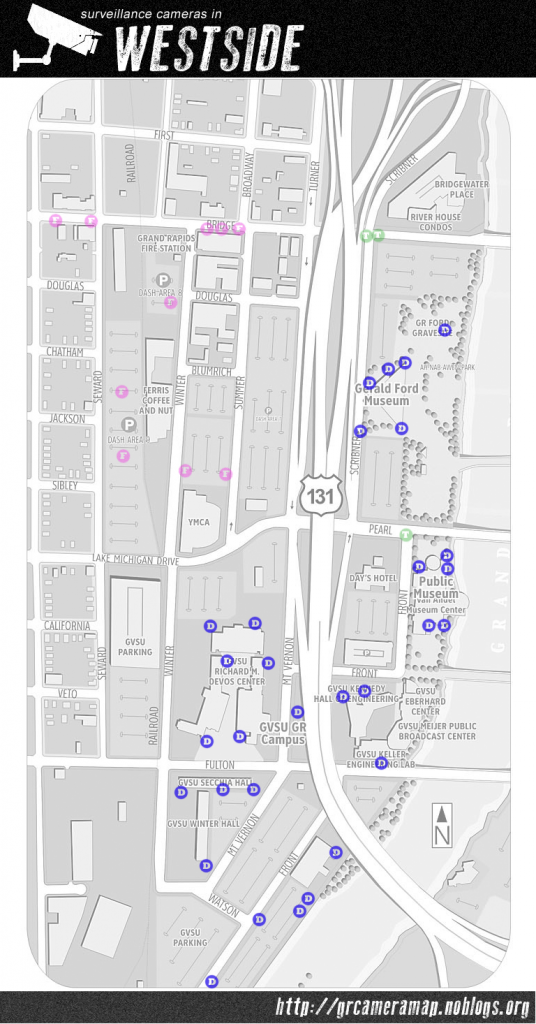

The policing functions they perform were discussed by Downtown Grand Rapids Inc. (DGRI), which operates the Ambassadors, stating “The Safety Ambassadors are intended to complement and enhance the efforts of the Grand Rapids Police Department.” DGRI CEO Kris Larson also said the program “works hand-in-hand with the police department, serving as their eyes and ears.” This is confirmed in their annual report, which claims that the Ambassadors have reported “suspicious people” 1,861 times. At a recent “State of the Grand Rapids Police Department” speech, the GRPD stated that working with the Safety Ambassadors has been “very positive for policing.” The statement is an unequivocal testament to the policing role of the Ambassadors.

Policing Without Police

Police violence and cases of excessive brutality have become apparent to a wide range of people since the rebellions that broke out in response to the police killings of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. It is possible that this is the beginning of an evolution of policing, where the Downtown Ambassador program or something similar can widen and accomplish some of the roles of policing without the threat of police “overreaction” and brutality. If the present trend can be described as wealthier white people moving back to the cities and crowding out the poor then the Downtown Ambassadors will serve an important role in facilitating this transition.

Though they are not legally permitted to use force or make arrests, the Ambassadors have a close relationship with the police. Manager of Operations for the Downtown Ambassadors Melvin Eledge says,

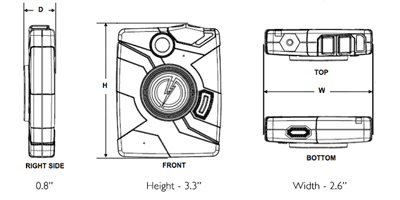

“Each of the Downtown Ambassadors is equipped with an iPhone and an internal app which allows them to build a report on each person of interest, creating a trail that helps the Ambassadors keep an eye on suspicious activity, hotspots and – just as importantly – to follow up with services people may have received to see if they need additional help.”

This surveillance function of the program allows the city and police to have more “eyes on the street” (an appropriation of Jane Jacobs’ language that replaces an authentic urban fabric with an artificially created one) while doing so under the guise of a form of social work. This gives the city a good image while also widening the scope of the GRPD’s ability to track and understand what’s going on at a street-level.

The visibility of homeless people directly contributes towards a city’s image and acts as a deterrent for wealthy people to become residents, especially if they are forced to interact with them face-to-face when being asked for money. As it is now, expecting the police to remove the homeless is a lot to ask in that it drains resources and initiates a process of brutality that would tarnish the city’s image. Urban police departments—while always guardians of property and power—cannot provide the level of “service” conducive to business development in a “troubled” area.

The Ambassador program is a logical solution for the city government in that they will try to stop panhandling and keep doorways clear from people sleeping in them. The Ambassadors recognize this goal, with Eledge stating “One aspect of the Ambassador program is making sure downtown residents are not constantly being asked for money as they go to and from home and work.” MLive says about ‘Downtown Safety Ambassador of the Year” Veronica Aho “for panhandlers, Aho keeps them moving along if they bother pedestrians.” As a result the Ambassadors made “3,806 panhandling contacts” in their first year.

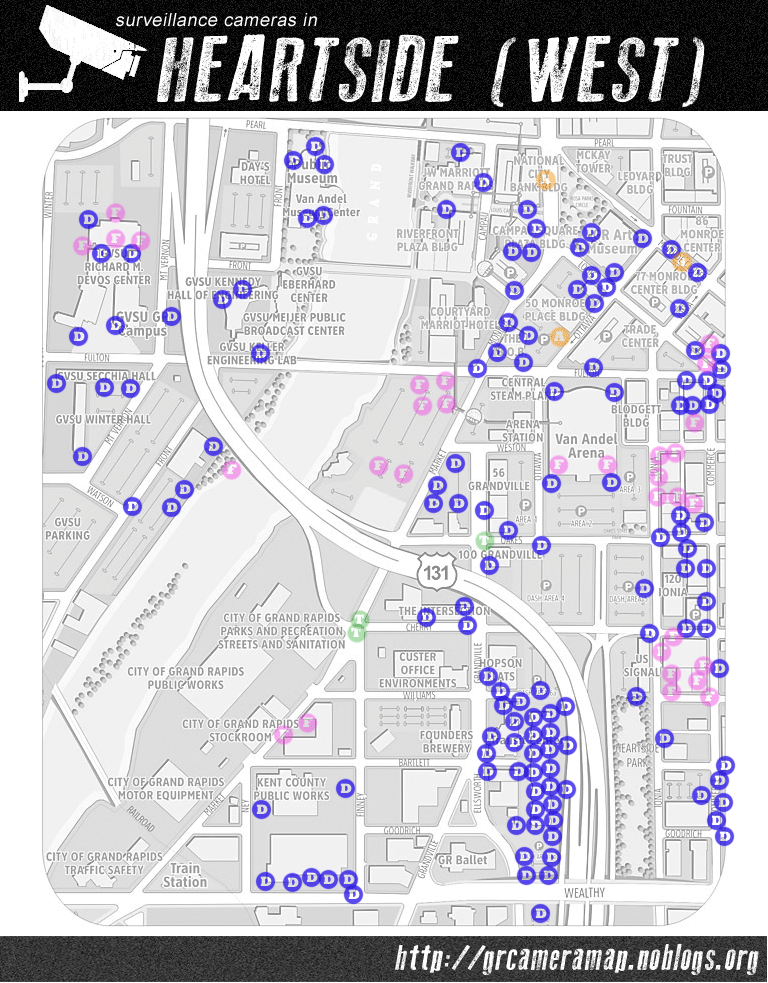

Of the seven Ambassadors, six of them rotate between different areas, while one is permanently situated in the Heartside district. Why the special treatment? This neighborhood, home to low-income housing, shelters and missions alongside boutiques and bars, is a place where the tension between business interests and human interests is especially visible—and requires special management to keep invisible. While the Downtown Ambassadors would describe this as unbiased “customer service” it is a policy function in that it manages—or gives the appearance of managing—a persistent social problem.

The city becomes a blank space on which commerce can happen—a predictable and safe environment.

In addition to “cleaning up” downtown by managing undesirable populations, the Downtown Ambassadors also physically clean up space. Unlike the police the Ambassadors have the ability to clean up graffiti when they see it, and they apparently did so in 1,462 instances during their first year. Graffiti arrived as a cultural phenomenon with the birth of hip-hop and its rising influence among urban youth during the 70s and 80s. It is an easy way for marginalized people to leave their mark on an otherwise hostile and alien world. As a blemish on an otherwise clean and orderly backdrop, it signals that the forces of order are not as invincible and omnipresent as they’d like to seem.

Not only do these reasons make it natural for the city government to want to remove it, but a graffiti-free area is also more appealing to out-of-towners with money who find graffiti to be off-putting, unsafe, and a form of blight. In this way the Ambassadors are performing a quasi-policing function that also helps gentrify the city. The city becomes a blank space on which commerce can happen—a predictable and safe environment.

Downtown GR: City or Mall?

Customer: noun

- A person or organization that buys goods or services from a store or business.

- A person or thing of a specified kind that one has to deal with.

Recently spokespeople for the Downtown Ambassadors insist that they are not an auxiliary police force and urges people to view them as a type of ‘customer service’ that exists for pedestrians in the downtown area. As it turns out the city can have their cake and eat it too. Making white and/or middle and upper-class people feel safe downtown requires both sanitizing the existing space in addition to providing a mediated, tailored experience. Whether they’re giving out-of-towners directions or reporting a “suspicious person” to the police, the Downtown Ambassadors are performing essentially the same task of making Grand Rapids more appealing to wealthier white people. This was made clear when DGRI CEO Larson said, “Frankly, there’s a lot of youth that have begun to hang out. It’s not the patrons of the bars; it’s the other element that is coming down looking for trouble.” In other words, those who want to spend freely at the bars are fine—and the Downtown Ambassadors exist to serve them and those who profit from them. Stellafly Social Media interviews Kris Larson and states:

“Larson has about the same interest in parking lots as he did as a kid. Parking lot? Pffftttttt. That’s no fun. Let’s build cool stuff on ‘em, he says, places where you can go spend your allowance.”

This quote evokes imagery of the ideal person downtown meant to be like a child at a toy store, whose relationship with the area is one of awe and passive consumption. A kid doesn’t loiter in the toy store or do anything there except browse and spend money. This is not only telling of what downtown is meant to look like but also of who is meant to be there, those with expendable “allowance” who can buy a $12 bag of pasta. This is why in all their interviews with the media DGRI refers to the Downtown Ambassadors as “customer service.”

In an interview with Wood TV 8 Kris Larson says the point of the Ambassadors is “really to provide that unexpected level of customer service to differentiate the experience in the downtown.” Eledge tells the Grand Rapids Press, “Everything we do, we do through a hospitality lens. We don’t act like security officers. It’s all about customer service, meeting their needs.” He echoes this sentiment later with Rapid Growth Media, “We’re out there for hospitality and customer service, and we include a safety and observation function.” For those with money it’s friendly service, for those without it’s a fast-track to social service programs diagnosed by security guards who repeatedly say they “aren’t social workers” and “aren’t cops.”

Just like the greeters at Meijer, they are both a human face to the business and a subtle form of loss prevention. If the Ambassadors represent a phase of urban development that views people downtown as “customers,” then in this plan the downtown space itself is meant to be a fabricated playground for consumerism. Urban settings are seen as exotic by white middle-class suburbanites. The growth of artisan culture perfectly coincides with this concept. Local shops and restaurants with handmade ingredients contrast greatly with strip mall chain businesses, while bike lanes and sidewalks pair well with feel-good consumer politics and resonates with those tired of sitting in traffic while commuting to work. Localism is ultimately just consumerism branded with a hip aesthetic.

Grand Rapids is now allowing and encouraging the construction of parklets, parking spaces turned into extensions of the sidewalk meant for people to stop, to sit, and to rest while taking in the activities of the street. Seating in the center of the mall come to mind, where customers can relax before getting up and going back to shopping. Recent and proposed park renovations also exemplify this, with Monument Park being remade into an extension of 616 Lofts and Veterans Park—long a gathering place for low/no-income folks in downtown—slated to undergo a similar transformation. For the newcomers to downtown “exotic” is good, but too exotic can be scary or overwhelming, and that’s where the Ambassadors come in.

The loss of kinship and community that exists in modern times is apparent in the fact that the Ambassadors exist at all. They are specialists in giving directions and offering warm welcomes, customs that in any other time would be done between strangers walking past each other on the street. The wealthier people new to downtown are afraid to interact with more disadvantaged long-term residents, while the latter have little interest in them. The Ambassadors are the friendly face that, for good reason, the new wealthier downtowners will not see on the current residents.

A Welcome Banner for the Rich

Going to the mall or shopping at a chain store creates strange feelings. Everything is ordered and designed in painstaking ways for the consumer to consume. The greeter welcoming people in makes the experience feel even more sterile and unnatural. The Downtown Ambassadors represent a vision for the city that wishes to treat its subjects in a similar way. We are meant to be customers of the mall that is downtown.

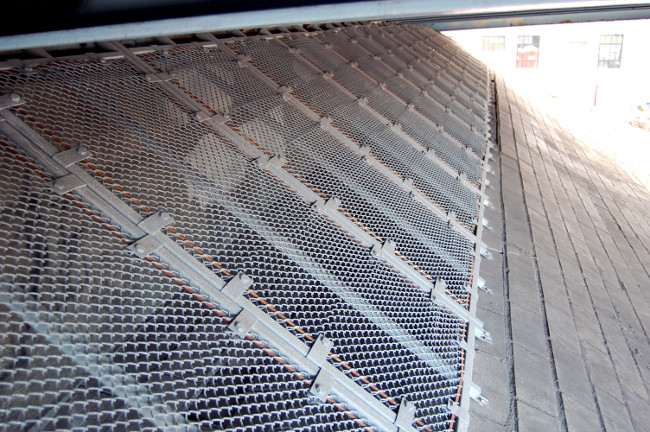

For now the city must grudgingly manage those who are unable or unwilling to be its customers. Criminalization of homelessness and arresting panhandlers and loiterers would bring bad press to the city. Instead little steps are taken: the fencing off of underpasses where homeless people slept near the new Downtown Market is one, a Downtown Ambassador shooing away a panhandler is another.

They may claim now that they are not an auxiliary police force but their management of panhandlers, their treatment of graffiti, and their close relationship with the GRPD says otherwise. Like the police, the operations they perform are for the benefit of business–in this case the downtown business owners, housing developers–and ultimately to pave the way for the next phase of capitalism.