“When you think of Downtown Grand Rapids and the Grand River, do you find yourself thinking about what’s there now, or do you imagine the potential of what could be?”

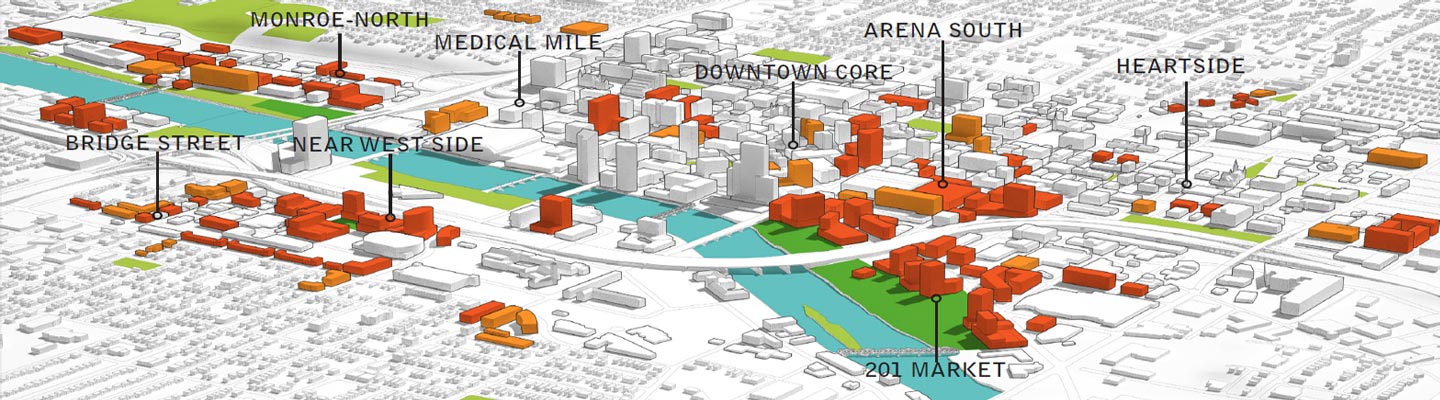

This is the evocative question posed by GR Forward, a “comprehensive planning process” that is creating an updated vision for Downtown, the Grand River Corridor, and the Grand Rapids Public Schools. GR Forward is a partnership primarily between the City of Grand Rapids government and Downtown Grand Rapids, Inc – though with 132 people working on the three committees within the planning process, the list of organizations involved reads like a spilled bowl of alphabet soup: DDA, DGRI, GRPS, MDOT, GRIL… It’s one giant board made up of smaller boards made up of board members from other boards. And together, with the help of “community engagement,” they’ve spent the past year and a half drafting a beast of a plan to reconfigure most of the riverfront so that it’s accessible and can be used for recreation; to bring more event programming, businesses, and (primarily market-rate) housing to downtown; and, almost as an afterthought, to renovate and expand a couple of the specialized public school programs in order to “retain and attract families, talent and job providers.” The draft has already been approved by all the appropriate city boards and commissions, so now it’s up for public review and comment until late September, when it will go back to those same boards and commissions to be voted on for adoption.

Lip Service to the Community

The GR Forward plan envisions a meticulously planned downtown, and consequently, the process itself was meticulously planned and facilitated. It was a well-designed process with slick advertising and an aggressive public relations campaign. It had all the right buzz words: engagement, community, stakeholders, decision makers, developers, businesses, non-profit and institutional partners, and the ever-so-important use of social media. In the end, they boast of having “engaged” over 3,600 people. If you attended one of their neighborhood meetings, you were treated to snacks, pop, and a lengthy presentation about GR Forward. Despite the lip service given to community input, the sessions laid out their vision for the total transformation of downtown. Following the presentation, there were some confusing “games” and “activities” to “facilitate” “engagement”, but the entire time, something felt off. There was a distinct sense that much of this was already decided and that the “input” really wasn’t going to change anything.

Perhaps this was why so much of it seemed to be talking down to those in attendance and why there was such a strong divide between the “experts” and “the residents”. It seemed to be more based on getting people to buy in to the plan rather than crafting it. For example, was anyone really supposed to believe that if they said they didn’t want the whitewater park, it would be excluded from the plan? Grand Rapids Whitewater was, after all, a partner from start – and surprise, surprise, work is already starting on that process. With much of the plan hinging on the Grand River and redesigning the waterfront, it’s also interesting that the City of Grand Rapids has already committed to building a portion of the riverwalk using GR Forward’s designs, even as the plan is up for community debate and discussion. The entire process seemed geared to encouraging more of what exists now: more market-rate housing, more hip restaurants, more local beer, and more scripted events.

Gentrification as Colonization

The GR Forward plan, despite its nods to diversity and opportunity for all, is a stunningly comprehensive plan for accelerating the gentrification of downtown Grand Rapids. This much should be obvious based on our understanding of gentrification. We know that the process of gentrification is generally spurred by a “paradigm of profiteers” made up of public officials, realtors, bankers, and developers, but that public officials (like, say, city planners and development authorities) are often the “chief architects” through initiatives like tax credits, grants, and policies (or, say, dreamy master plans). We know that the process invites entrepreneurs and investment into previously disinvested areas, and lures prosperous residents with new offerings like trendy eateries, wine bars, and cleaned-up parks. We know that this drives up rent and prices, changes the culture of the area fundamentally, and drives out previous residents.

But an idea as large as gentrification still seems to fall short when describing the totalizing scope of the plan and the motivations behind it – in how it reaches down through people and buildings to the land itself. It reeks also of colonialism, and indeed, gentrification can be understood as a modern expression of colonialism. As Jonathan L. Wharton writes, “While modern man might argue that today’s civilizations no longer have colonization in the antiquated sense, gentrification is the modern version of modern man’s obsession with land acquisition.” In gentrification as in colonization, those with power (be they developed nations or development firms) take possession of an area for their own benefit, with no regard for, or only self-serving interest in, the history and heritage of the area. In gentrification as in colonization, pre-existing culture is reshaped and destroyed in the name of improvement. Both processes rely on consumers (be they settlers or “young creative professionals”) who are generally unaware of or misunderstand their role in the process. And both processes result in a lose-lose choice for the previous residents: stay put and face marginalization and ever-increasing pressure, or leave.

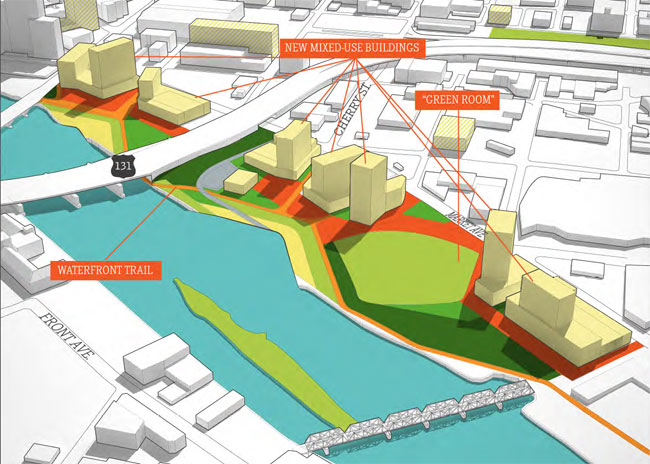

Like any city’s master plan, the GR Forward plan seeks to rearrange existing space, services, land, and populations with an omnipotent hand. Not only would existing residents continue to be displaced under this plan, services like the U.S. Post Office on Michigan Street and the Public Services offices and storage area on Market Avenue would need to be relocated to make space along the river, the riverfront would be completely remodeled, and even the river itself would get reconstructive surgery. Beyond the question of whether these changes are good or bad lies the fact that downtown Grand Rapids is seen as a game board or blank slate upon which the whims of profit-driven authorities can be worked and re-worked. Why should they have that power? While there’s plenty to critique in the details of the plan, it’s this colonialist way of thinking about the world that enables any of it to happen in the first place, and which needs to be challenged and resisted with the greatest strength.

Excessive Control and Bureaucracy of Urban Space

GR Forward’s plan is for the control and management of urban space. While the plan speaks to the importance of vibrancy, cultural expression, and life in urban spaces, in actuality it limits them. It presents a vision of highly structured, managed, and bureaucratized public space—it’s the vision of a group of people who want to manage everything, who just can’t seem to let go and let things happen organically.

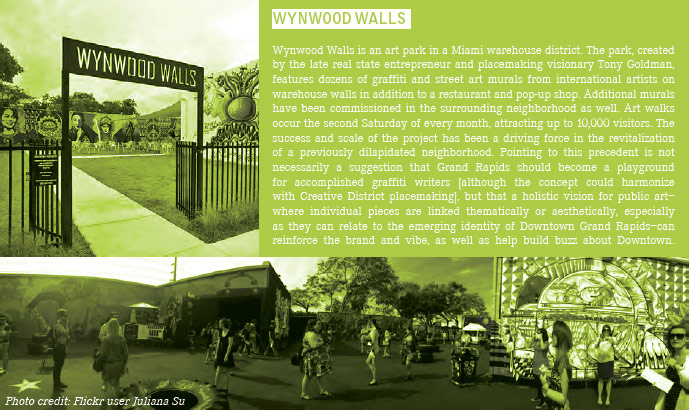

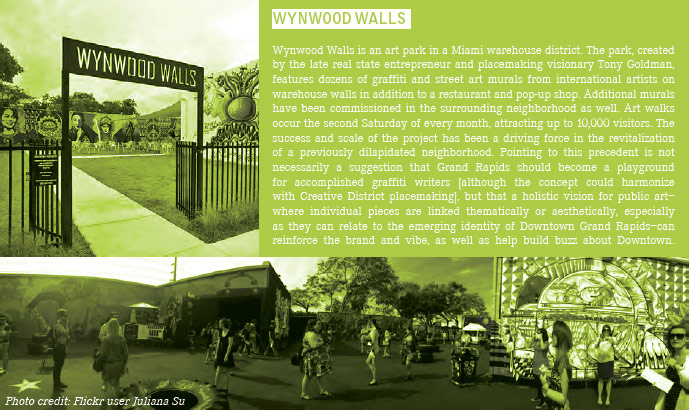

The big cities that many in Grand Rapids look towards as models are characterized by a genuine sense of unpredictability. People mix, forms of culture appear spontaneously, events happen without sanction. The most vibrant and exciting urban areas are often characterized by chaos: musicians play on the street, people gather, graffiti and street art appears without sanction, vendors are everywhere, people break dance on street corners, etc. There’s a lack of structure, a lack of cleanliness, and a certain “edge” that simply doesn’t exist in Grand Rapids.

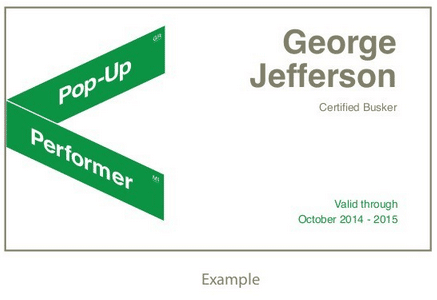

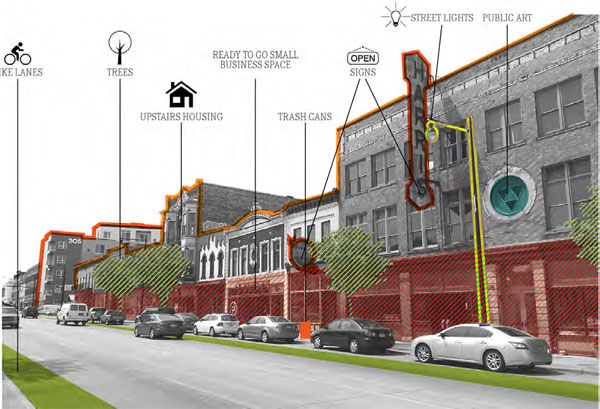

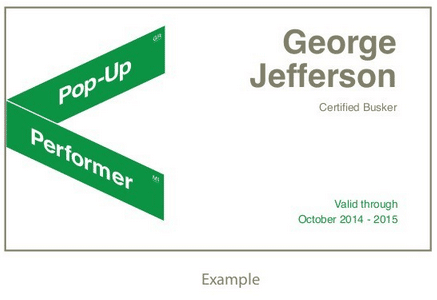

In contrast, Grand Rapids—and GR Forward—presents a constructed vision of pseudo-vibrancy. Rather than a group of people showing a movie in their favorite park, we get the highly structured “Movies in the Park” as an official program. In place of improvised bucket bands, we get licensed “Pop-Up Performers”. In place of a vibrant underground art scene, we get “Public Art” (or even planned “street art”) and the attendant committees, rules, and regulations. Rather than simply gathering in the park, there is the facilitated “Picnics in the Park” series. We get the “programming” of downtown—a seemingly endless sequence of highly planned and coordinated events to appeal to a specific series of demographics. These modes of expression are to be commercialized, with an intertwined relationship between the “event”, “the sponsors”, and “the businesses” that surround it. Does the event exist for its cultural values, or for its potential economic ones? We get the constructed vision of “downtown as product.” It’s squeaky clean, it’s “family friendly,” and there is plenty of parking (for either your car or bike). It’s the “city as entertainment machine,” where culture is primarily a means for generating economic activity.

They Might As Well Charge Admission

If GR Forward has their way, all of downtown will be molded to their liking, and as a result the experiences we have will reflect that. The micromanagement implied in their plan is so meticulous it’s as if they played Rollercoaster Tycoon or Sim City all night before their planning sessions. “Gateways” welcoming people into “branded” neighborhoods and districts, like the ones at Disneyworld, are suggested for 13 separate roadways or underpasses downtown alone. They want to light all of the city’s bridges and adorn blank walls with LED lights. The signs and flashing lights will make it abundantly clear, we are experiencing downtown as a theme park or playground – where “fun” is engineered for the purpose of generating a profit.

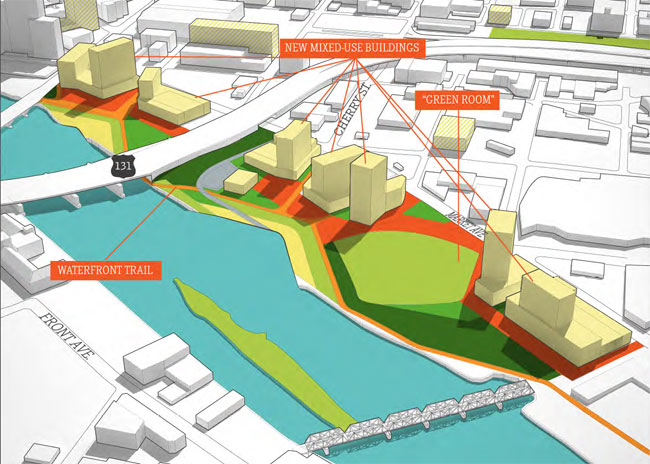

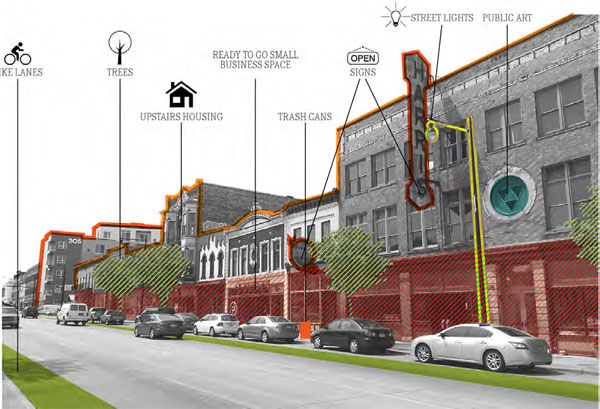

Heartside Park, considered an obstacle to the city’s goals, is proposed to have gardens, lighting, a skate park, a hockey rink, curling courts, and a sledding hill. Similarly Calder Plaza is to have new seating, “mobile landscapes,” and a “Health Loop” around it connecting the Medical Mile to the river. Parklets are suggested for Monroe Center, Ionia Avenue, Commerce Avenue, Bridge Street, and Pearl Street. Bridge Street is to have façade improvements and signage, as well as a skate park underneath its 131 underpass.

Street furniture, lighting, signage, and landscaping are suggested to “upgrade” Fulton, Bridge, Pearl, Cherry, and Wealthy Streets, as well as Market and Division Avenues. Market Avenue is proposed to get a landscaped median. Public art and LED lights are suggested to cover highly visible blank walls. Even winter isn’t untouched, with proposed winter food trucks, winter parklets, and even “warming huts” being hinted at, to keep shoppers warm while walking downtown. They even suggest moving those big mounds of snow that pile up against buildings and putting them to recreational use!

The chances for spontaneity and the development of organic relationships with space dwindle with the level of management that GR Forward is putting forth in their plan. As we wrote about in “Ambassadors For Whom?”, highly organized space is the domain of malls or theme parks. These privately owned businesses are designed to facilitate a standard experience for consumers, specifically one that makes the owners the most money. It appears that GR Forward and other modern urban planners and developers are, consciously or not, borrowing their techniques.

Obstacles to Brand Rapids

GR Forward ultimately offers an exclusive vision of downtown Grand Rapids. It’s one that caters to the young professionals, the tourists, the empty-nesters, and the coveted demographic de jour. The downtown as playground metaphor only works if that playground has willing participants, but to get to that point, there must be removal and exclusion.

Even the “progressive” and “inclusive” language of GR Forward’s best PR people can’t hide the fact that there are currents in downtown that run contrary to GR Forward’s goals. One of the best examples is the Division Avenue corridor and the Heartside Neighborhood, which remains a persistent problem for the would-be gentrifiers and the colonizers of urban space. The area is home to those without homes, low- and no- income residents, and the social services that help sustain them.

It’s no surprise that GR Forward identifies the Division Avenue corridor as an area that needs “improving.” But as is often the case with generic calls for “improvement,” the language is coded. In this case, GR Forward makes it clear that its primary concern is dealing with perceptions that the area is “unsafe.” Thus, the plan calls for numerous efforts to make the area “safe.” The question is of course for whom should the area be safe? Those who live in the vulnerability of life on the streets and the copious dangers that can accompany that life—or for the new economic transformation of downtown? As one might expect, GR Forward talks about creating a so-called “true mixed-income district” but the focus is primarily on the safety of commerce, the new downtown residents, and those who visit the area. It calls for the further expansion of the Downtown Ambassadors program, which has been adopted as a soft form of policing to manage low-income and homeless peoples’ effect on business. It speaks of incentives for business expansion, new apartments for “young professionals,” new street lighting, and other efforts aimed at improving “perceptions of safety.” The problem is of course that these are often small steps towards gentrification and they will displace people over time, creating a phenomenon—already documented in Heartside—where long-term residents will feel like strangers in their own neighborhood.

Moving beyond Division Avenue, Heartside Park is identified as a special area of concern. Since its creation, the park has been a gathering spot for Heartside residents, although tensions between police, residents, and new developments have existed almost since its inception. The tensions increase with each new development as the area experiences a culture clash. GR Forward frames the park as an area that “needs improvement” noting “…the current use of the park for illegal activities … has fostered negative perceptions about the park and the surrounding area.” They assert that the park “…needs more programming and people to root out the activities that deter use of the park.” But as in the case of much of GR Forward’s plan, it sounds like a road map for further displacement, replacing one group of people—who hang out in the park because they have nowhere to go—with another who want to enjoy the park as an “urban amenity” to a new 21st century lifestyle. People should be having picnics with goat cheese and wine from the Downtown Market in the summers, not playing basketball on the courts (which appear to be removed from the redesign of the park). One can already see the lines drawn in Heartside Park with well-dressed Market patrons eating $4 ice cream cones on the far southern edge of the park, while a completely different crowd in terms of demographics, hangs out at the other end.

A Failure at an Impossible Goal

Words like “diversity,” “accessible,” and “inclusive” are sprinkled throughout the GR Forward plan. Planners heard a “constant refrain” of people saying they want a downtown that is “welcoming and inclusive,” hence so much agreeable language. However, the plan is at odds with the ideas of “diversity and “inclusion” as it presents a vision that is for the benefit of those with economic power (a form of power that that often correlates with others, pertaining to gender, race, and class). In a highly imbalanced society dominated by structural and implicit power structures, it is largely impossible to create a plan for diversity, inclusion, or accessibility. For an organization that can get so specific about things like trash cans and the design of light fixtures, it is nevertheless telling how little GR Forward says in this regard.

Take the proliferation of events and entertainment options advocated by the plan—how can it be that an effort overseen by so-many well-paid consultants, organizations, and PR people could say nothing about having culturally diverse forms of entertainment? Is this an intentional exclusion—a rather subtle yet keen acknowledgment that the new downtown is to cater primarily to white tastes—or just an incredibly bad oversight that highlights a major underlying flaw in their vision of the “new” downtown? The emptiness of the diversity discussion is also apparent in the plan’s approach to housing and affordability. They embrace the continued development of so-called “market-rate” housing in downtown, as if “the market”—motivated entirely by profit—will ever embrace diversity in more than a token way. More disturbingly, while the plan offers words in favor of “a mix of housing types” and “a mix of incomes,” it seems considerably more concerned with the need for “more income density” (read: more people with higher incomes). In their discussion of housing affordability, they argue that part of the problem is that “affordability” is inherently hard to define. They even assert that “what is affordable to one family is not to another.” While objectively true, they sound a lot like the developers marketing $700-$800 studio apartments as affordable.

There’s also cause for concern when the plan advocates for housing for the so-called “missing-middle” that is excluded from low-income housing and can’t afford the high-end of “market-rate” options. The limits of this were shown quite clearly in the Grand Rapids Press when reporter Jim Harger urged readers to feel the pain of a couple who just couldn’t manage to find an apartment in downtown until 616 Lofts came along to fill that void with a 2-bedroom offering for $1,400 a month. While the plan does claim to support the increased development of affordable housing, it places its faith in the market, hoping that incentives will encourage developers to incorporate affordable housing and that more development downtown will create jobs, which will in turn increase incomes. Of course, if the solution was just as simple as getting a better-paying job, people wouldn’t need low-income housing in the first place. How many people living in low-income housing or on the streets are going to be able to get a job as a web developer in the new downtown economy?

Exploiting the River

Most people living in Grand Rapids, including those living downtown, don’t notice the Grand River. It’s caged by cement flood walls and hidden behind buildings. Consequently, there is a certain amount of appeal to some of the ideas presented by the GR Forward plan. Given the current state of the river, who wouldn’t want more parks, semi-public spaces, and less flood walls? However, at its core the plan really isn’t about the “beauty” of the river or even the river itself. It’s about “activating the river” which is just a nice way of saying making money off of it. This is a familiar story, one that began with the colonization of the Grand River Valley by white Europeans. The settlement of Grand Rapids was based in part on the river and the ability to use the river to generate wealth and dominance. For the early part of the city’s history, this was based primarily on logging. By the late 1800s the trees of Michigan were felled, changing its landscape which now accommodates cities. Lumbering in those days was viewed as infinite, yet it only took 20 years to cut most of the state’s forests. Over the years this shifted to furniture production, but in either case the river was at the center as an economic force.

For many humans, the story of the river has long been about molding it and shaping it to suit our perceived needs. Whereas we once floated logs down the river to support an industrial economy, GR Forward is talking about sending kayaks down the river to support a post-industrial economy. As industrial production declines here in the U.S., leisure activities have become economically important to cities. Like the past lumbering relationship to the river, the one envisioned by GR Forward is predicated on the “needs” of the economy. The entire discussion of the river is filtered through an economic lens. Everything raised in the plan regarding the river relates to this question. It’s all about the river as a “game-changer” that can be a “catalyst for development”. So in other words, how they can shape the river to encourage developers to build more high-end buildings and invest along the river. Even the planned whitewater park (and white it very much will be!) is a way to attract well-to-do outdoor enthusiasts with money to spend in the city. GR Forward may talk about the emotional and physical connection one could have to the river, but our relationship with the river is always shaped by economic forces, and for most of us is no longer guided by spiritual or deeper, ecological understandings.

The GR Forward planners hope to “reestablish the emotional and physical connections between downtown and the river that Grand Rapids was built on.” A touching sentiment. Truly, people in urban environments are very disconnected from the land they live on. Having access to and spending time around natural elements can not only be calming and moving, it can help us feel connected to the larger world or stoke a deeper sense of our role within it. Encouraging an emotional connection to the river could be very powerful in this way. But the connection to the river “that Grand Rapids was built on” was not one of reverence or respect – it was exploitative. As previously discussed, most cities that are established alongside rivers grow there because the river is an access point for trade, which helps give birth to industry and commerce – powers that often conflict with human need and environmental balance quite profoundly. So do the GR Forward planners want to restore connections with the river for the good of the river, or for the good of the economy? In the long term, it can’t be both.

Activating and Commodifying the River

The draft plan talks about “activating” a number of sites – we should “activate” the river, “activate” river-adjacent parks, and “activate” downtown in general. The term seems strange at first, implying that these sites are currently inactive. The river, coursing and churning and teeming with fish and microbes, while certainly much different than it was before it was dammed and tamed by industrial power, seems perfectly active already; it is a living thing with a loud voice. People populate every park and green space near downtown, at least in the warmer months – fishing, playing games, socializing, resting. Parks are one of very few neutral spaces in the city where one can simply exist without spending money, so those without money to spend often pass time there, in addition to the usual joggers and workers on break. These places are active and alive already. The “activate” refrain begins to make more sense when you realize that the term is used by the PR-savvy city planners as a code word for “commodify.” All the activations proposed in the plan are simply ways to get more money flowing through those sites: food trucks in the parks, more shopping downtown, rented kayaks, and tourists bobbing in the river. They don’t just want to draw more people to these places, they want to draw people who have money to spend – at the cost of isolating and displacing those who do not.

So, “when you think of Downtown Grand Rapids and the Grand River, do you find yourself thinking about what’s there now, or do you imagine the potential of what could be?” The GR Forward plan offers a limited set of options for what could be. Does the vision of a quirky food truck parked outside a new boutique store make your heart stir? Does the sight of the presidential museum looming over the reconstructed burial mounds at Ah-Nab-Awen give you pause? When you think of the river swelling past its containments, do you imagine updated flood wall plans, or do you imagine the music of the current swirling past concrete?

In other words, while the Grand Rapids favorite “

In other words, while the Grand Rapids favorite “