Recently, amidst the increasingly clichéd announcements of upscale housing, breweries, coffee shops, and yoga studios coming to the rapidly gentrifying Westside, something different was unveiled. Many of the larger news outlets in the city (WOOD TV, WZZM 13, Mlive, and MiBiz) all reported that Rockford Construction – who is playing a major role in the gentrification of the Westside – was building an “affordable housing” project.

To read the news articles, one would get the sense that this project was an act of benevolent charity. The reporting focused on how Rockford Construction was responding to the westside community’s wishes. Mlive quoted CEO Mike Van Gessel, “We know that for us as a neighborhood, more affordable and quality housing is a need and an important part of healthy growth.” The affordable housing project, combined with the recent announcement that Rockford is hoping to build a grocery store on Bridge Street, gives the impression of a developer who “cares” about the neighborhood. The articles also play up the idea that Rockford Construction is looking for feedback from the community, in the sense that “we are all in this together.”

Digging Deeper

It makes a great story, but the reality is of course much more complex. Beyond the headlines and celebratory articles, the application Rockford Construction filed with the Planning Commission gives much more detail.

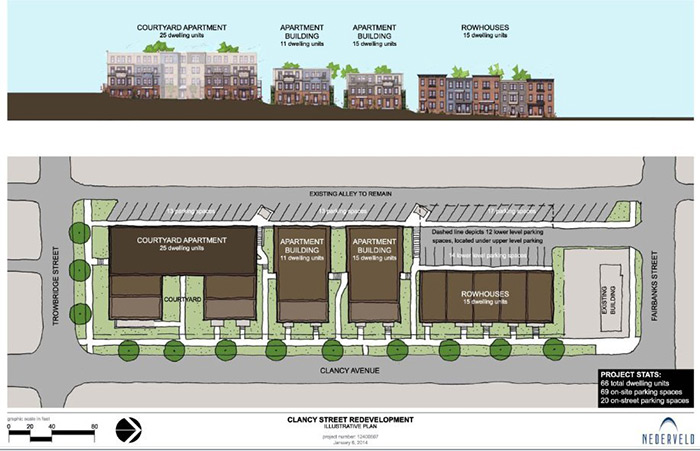

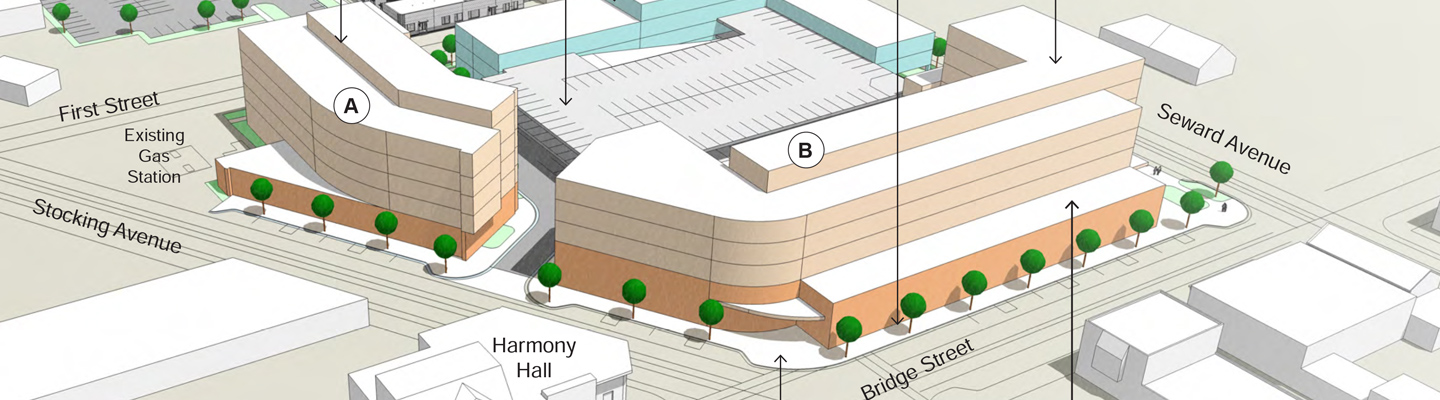

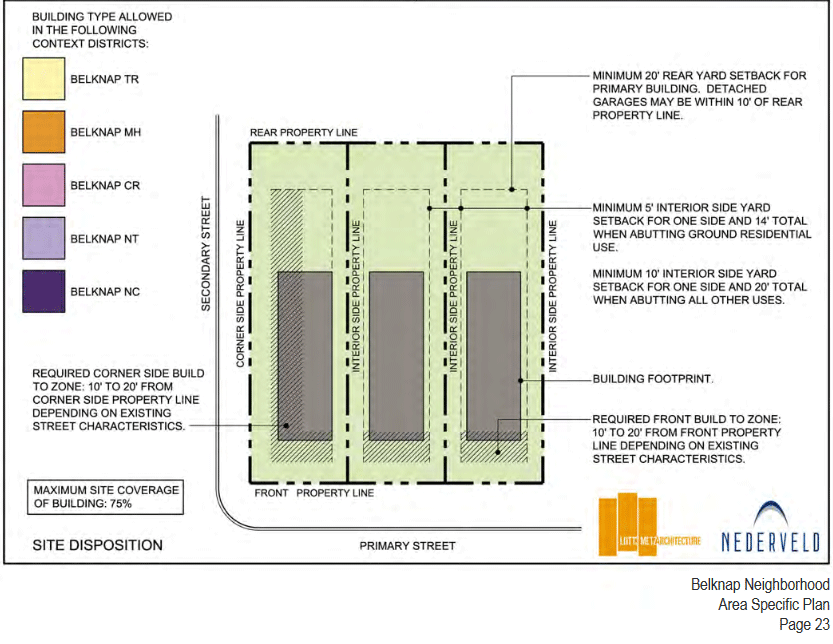

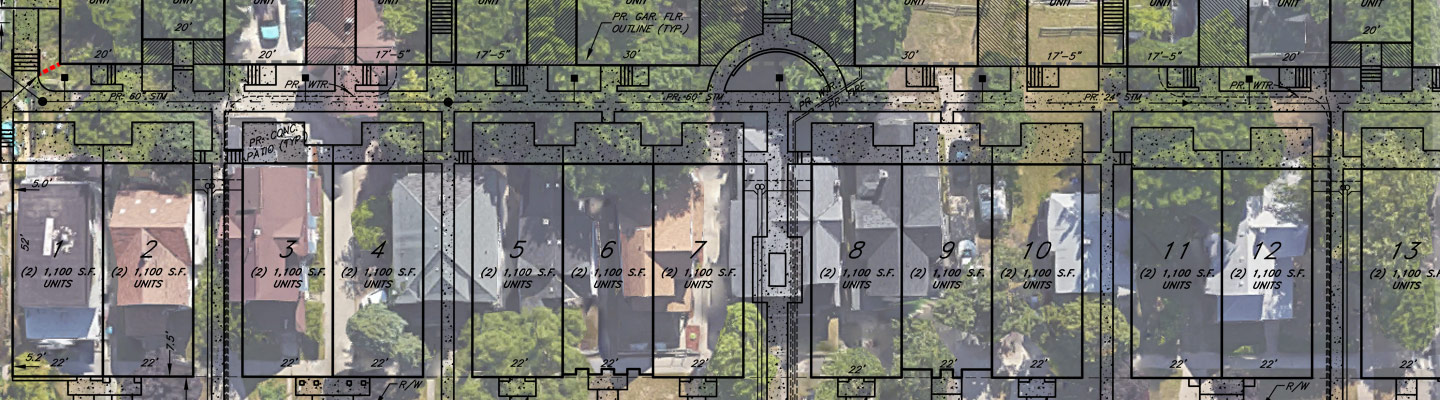

In order to build the development, Rockford Construction requested a zoning change for the area bounded by Stocking Ave NW, Bridge Street NW, Seward Ave NW, and 1st Street NW. The change would allow a building of five stories in height, as opposed to the current four-story limit. Technical details aside, the “affordable housing” component is just one small part of a much larger project. There would be a second building along Bridge Street constructed that would include four stories of housing atop a grocery store, none of which would be affordable.

The requests – while one is for “final” approval and the other for “conceptual” approval – were presented together in a single package. If funding from the State of Michigan falls through for the affordable housing, Rockford Construction will still build the housing – it just won’t be affordable. While they state that their “preference is for affordable housing units” in the first of the three buildings, affordable housing it gets scant mention and ultimately there is nothing holding them to that. Most of their application focuses on how they will be eliminating blight and increasing density and economic vibrancy.

Furthermore, the building containing the affordable units would be a “mixed income” building. This means that while the majority of the units would be “affordable” by state standards, others would be rented at “market-rate”. Most of the units would also be studios and one-bedroom units, making it a less feasible option for families, who are facing some of the worst housing insecurity. Instead, it would likely appeal to single people and couples – an acceptable demographic for the type of gentrification happening in the area. While the notion of “mixed income” is a mantra of New Urbanism and is taken as gospel, in this case, it means that there will be simply less total affordable units.

Academics studying urban development and gentrification have consistently questioned the idea that mixed income housing is a benefit to low-income and working-class residents. In the anthology, Mixed Communities: Gentrification by Stealth?, the various contributors discuss how despite New Urbanist fantasies, mixed-income neighborhoods don’t encourage mixing as people largely don’t interact outside of their class. Instead, they discuss how “mixed income” housing is often used as a way to “test the waters” for gentrification and introduce a new class of residents into traditionally low-income areas while avoiding criticism. It is almost always a one way move of wealthier residents into working-class areas – nobody speaks of creating “mixed income” housing in middle-class neighborhoods. In the worst cases, it can be motivated by a classist assumption that somehow by living in proximity, upper class residents will model good behavior to poorer residents or that the wealth will somehow “trickle down”.

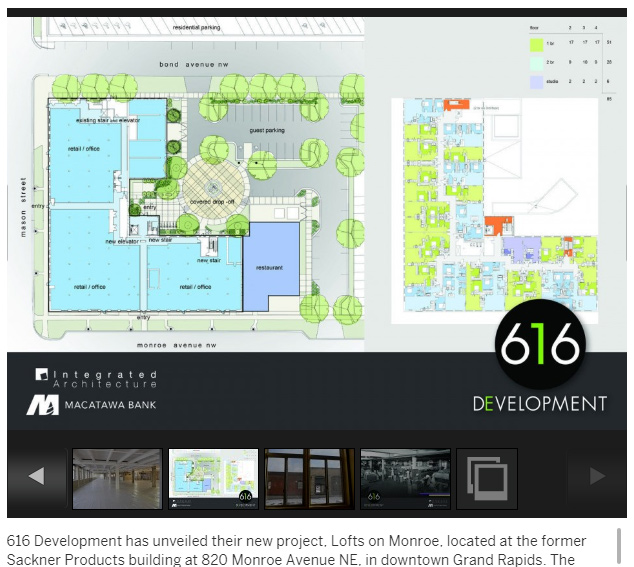

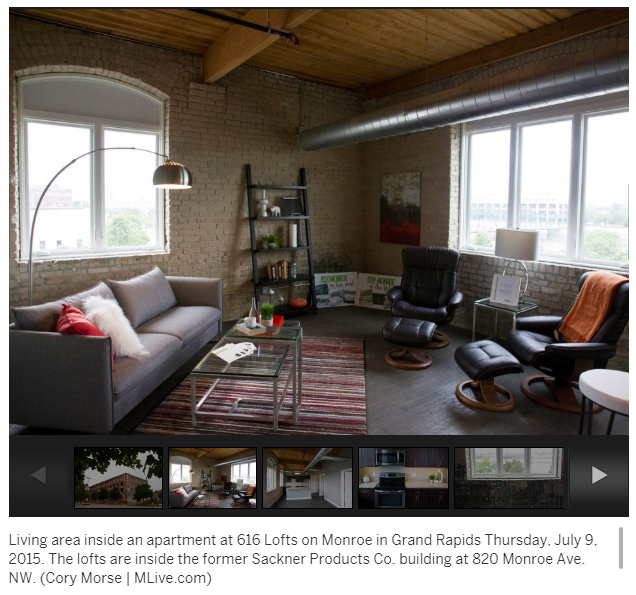

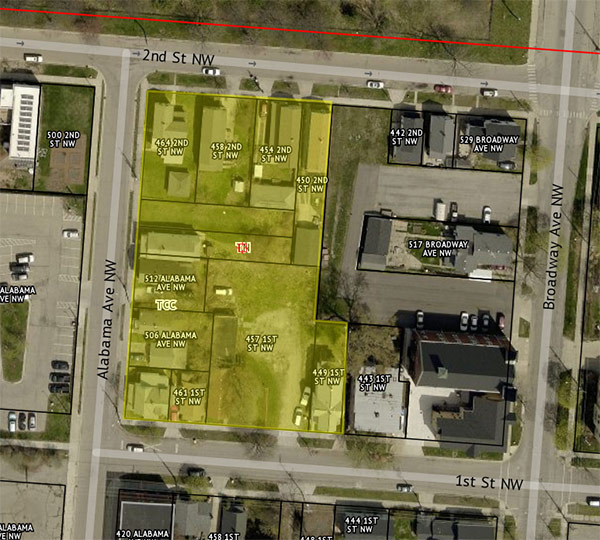

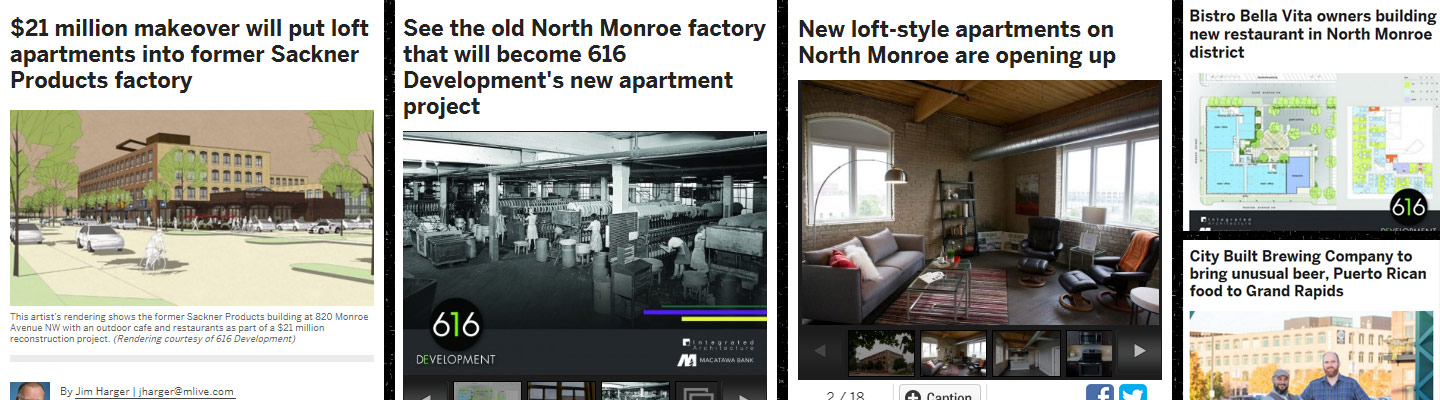

The Missing Context

Also missing from the news reporting is the fact that Rockford Construction is a major player in the gentrification of the Westside. Its projects – Fulton Place, 600 Douglas, and its partnership with 616 Lofts on Alabama – are bringing in a new class of residents, with “market-rate” rents that are synonymous with the rising unaffordability of Grand Rapids. For example, rental rates for a one bedroom apartments built by Rockford Construction in the area are $1,325 at Fulton Place and $1,150 at 616 Lofts on Alabama. Sixty units of affordable housing is an incredibly small portion of the housing they are building on the Westside.

With Rockford Construction buying up properties, boarding up houses, and developing plans over the past several years, the gentrification of the Westside has been a deliberate process. This is typical behavior for any developer.

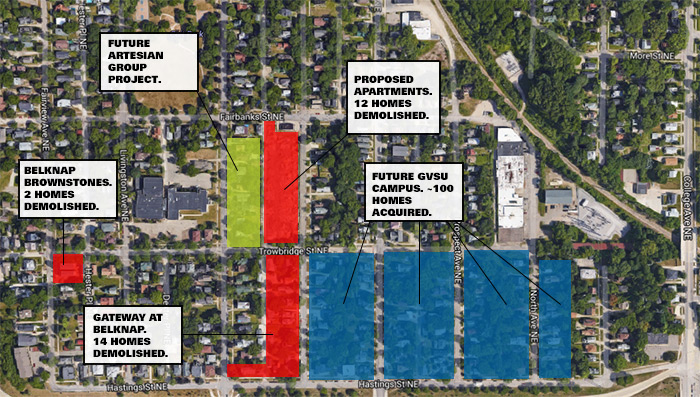

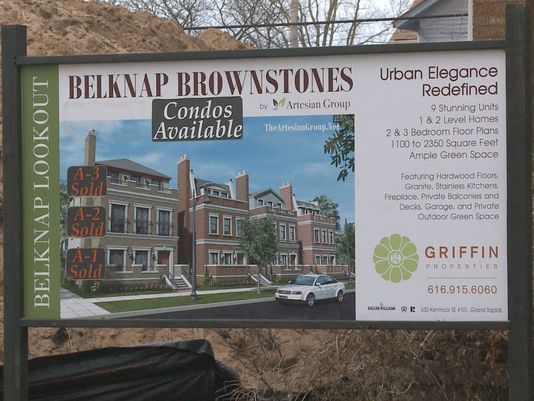

Rockford Construction has been drafting plans, particularly in the neighborhood north of Bridge Street and south of I-196, Of course, people still live in some of these homes, but those are mere obstacles to address – likely through demolition and the declaration that the homes are “obsolete”. Nobody would say that the residents are obsolete, but they will be made so as the area is transformed into an upper class haven. Proponents will no doubt say it isn’t an example of gentrification because it doesn’t follow some set formula they’ve decided must be present, but the neighborhood will be rebuilt in the image of the upper class. Perhaps a French word used instead of gentrification – embourgeiosment – does a better job of capturing what is planned for the Westside. It will be the creation of a place where bourgeois dispositions will be dominant, as opposed to its traditionally working-class character.

It’s similar to what Rockford Construction is doing on the southeast side, where a leaked planning document back in March showed detailed plans being considered for a large portion of the southeast side. Most strikingly, it spoke of “carrying excitement and activity from the Wealthy Street corridor” down Eastern Avenue and states that Rockford Construction should begin to “purchase parcels under various entity names”. Not surprisingly, many people were upset about the plans and sometimes contentious meetings were held. The charge that Rockford Construction was doing this without neighborhood consultation was frequently made and criticisms of the one-sided nature of development along Wealthy were also raised.

In this context of gentrification and outrage, it’s worth considering why the “affordable housing” angle took the lead on this story. It helps to deflect criticism of Rockford Construction’s overall actions on the Westside and gives a positive impression after the uproar over their plans on the southeast side. Few people will oppose affordable housing and a grocery store, while at the same time, Rockford Construction develops the rest of the block in a manner consistent with all of its other projects. It has the feel of a deliberate PR move, an escalation in an ongoing effort to silence criticism through the process of making donations to neighborhood entities and the hiring of a “Community Engagement Director”.

What Development Wants, Development Gets

This project – aside from the difference of using affordable housing as a hook to gain approval for a larger project of gentrification – played out similarly to how all developments do. As we explained in the article “Participation, Engagement, and other Illusions”, the City of Grand Rapids and developers don’t seek meaningful engagement, instead they consistently do the absolute minimum. This is as true with this project, as it is with any other. The final approval for the project happened at a 1:40pm meeting on Thursday July 14, which few people will likely attend. For proof of engagement with “the community”, Rockford Construction’s application to the Planning Commission includes a sign-in sheet from a board meeting on June 20, 2016 with the West Grand Neighborhood Organization. Of the sixteen people on the sign-in sheet, seven were board members, three were GRPD officers, and two were from Rockford Construction. Clearly, there was not much engagement and there is no summary of what was said. From a report on GRIID.ORG, a supplemental meeting on July 7th was perhaps even worse, with minimal information about the project presented and little opportunity for engagement while representatives from the City talked at the audience about development in general. In any case, it doesn’t even matter as the core of the plans were already made and nothing was likely to change, despite Rockford Construction’s declared desire in the media to listen to community feedback.

Of course, the reality is that everyday developers are making plans to radically restructure the neighborhoods of Grand Rapids and that they care for little beyond profit and their image. From the southeast side to the Westside, developers and the city have committed themselves to a project of gentrification. Heart-wrenching stories of rising rents, displacement, housing insecurity, and poverty abound, while at the same time, the city, the media, and the developers enthusiastically cheer with each demolition of a so-called “obsolete” building.

Development in the context of capitalism always will involve land-grabs, displacement, back room deals, and secret plans – it’s how it works. Developers can also readily incorporate simple demands for “affordable housing” or neighborhood services into their rhetoric, perhaps even building the occasional affordable housing project as a means of silencing criticism. Rather than having our imaginations limited by zoning acronyms, arcane legal codes, micro-units, City task-forces, non-profit lingo, and misguided notions of “pragmatism”, we need to start asking how we can build a new paradigm – one where we can truly thrive and where we aren’t pacified by the false hope that at some point developers and city leaders will voluntarily start building a “just” city. The history of Grand Rapids from colonization to present day segregation and racialized policing shows that it simply isn’t going to happen unless we challenge ourselves to develop new strategies of resistance and forms of living.

In January of 2014, The Grand Rapids Press published its first article on the project, titled “

In January of 2014, The Grand Rapids Press published its first article on the project, titled “