Recently, the final draft of the GR Forward plan was released. We wrote an extensive article critiquing many aspects of GR Forward back in August, but after a barrage of news articles touting the plan’s allegedly strong commitment to diversity and inclusion (The Rapidian and Mlive), it’s worth looking at again. Moreover, the plan is rapidly moving through various boards toward final approval. It recently passed unanimously before the Planning Commission on November 12, after being approved by the Downtown Development Authority (DDA) and the Monroe North Tax Increment Financing Authority the previous day.

To hear GR Forward tell it, the new draft is substantially changed: it is a significant response to criticism around the issues of diversity and inclusion. The basis of this claim is the new preamble titled “Towards an Equity-Driven Growth Model in Downtown Grand Rapids”. It’s full of seemingly bold, self-critical statements like:

“The robust public engagement process also revealed widespread concern regarding everyone’s ability to participate in Downtown’s historic and future prosperity. Put plainly, a broad swath of our community, including many from historically marginalized areas of the City, believe they’re not welcome or don’t belong in Downtown Grand Rapids.”

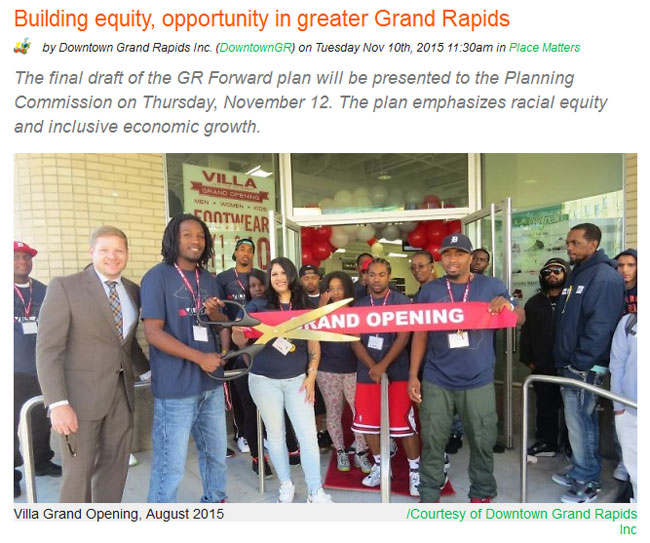

Based on news articles and GR Forward representatives, it seems like a major mea culpa. After a draft document that was embarrassingly bad on the topic of diversity, it’s now seemingly front-and-center. There’s calls for an African-American Heritage Museum in downtown, an African-American festival, diverse cultural events, and more. GR Forward wants more diverse city boards as well as a “regional equity framework” to address the ways inequality manifests itself across the region. There are calls for more minority-owned businesses and more minority workers in downtown. That’s all well and good, but they hardly seem adequate to the task at hand.

The United States was built on white supremacy and it is still a white supremacist society. “Diversity” is a terribly ill-suited approach to dealing with this legacy as it ultimately relies on the goodwill of employers, developers, city boards, etc, to decide if “diversity” is something worth having. It does not address the structural or material basis of racism and glaringly absent from the discussion is the fact that large portions of the “new” Grand Rapids rely on white supremacist divisions of labor: it is largely people of color who work in kitchens, do housekeeping, clean the streets, etc.

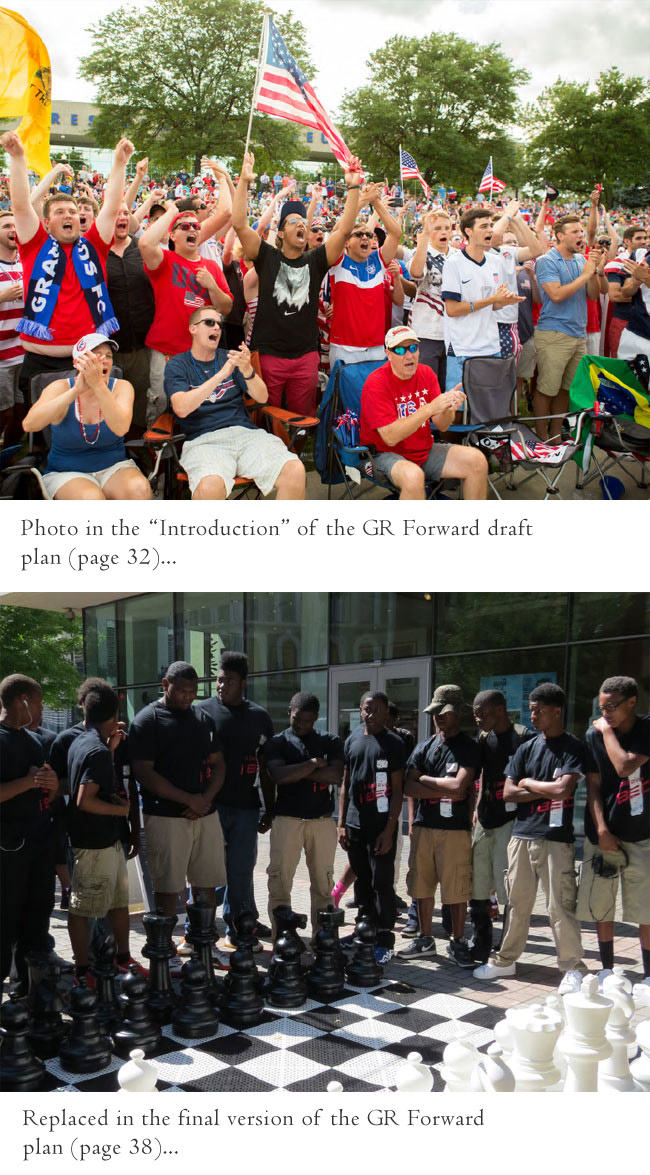

Even taking GR Forward’s approach on their own terms, there is nothing making sure that they will actually achieve the goals they identify, they are just targets . It’s just lip service at a greater scale: a preamble accompanied by more visible photos of minority populations. It’s something to show critics who justifiably raise questions (see their summary of public comments received on the draft [presented to the Planning Commission], they point people to this section over and over). It still reads as though it’s tacked on, a scrambling attempt to deal with the perception that GR Forward isn’t really about inclusion or diversity. And it isn’t now nor was it ever, it’s only ever been about economics.

In that sense, little has changed in the draft. It still advocates for the core project of transforming downtown and making it a more attractive destination for tourists and those who currently live outside of its confines. The same mantras are repeated about the “need” for 10,000 households to gain further investment (and what the city can do to get to that point), the necessity of “restoring the river,” the proliferation of staged events, etc. There’s no need to repeat these criticisms, they were laid out in our previous article on GR Forward. Despite the changes, it is a plan that seeks to transform downtown into a playground for the rich, or those who like to play tourist for the weekend while visiting downtown for ArtPrize.

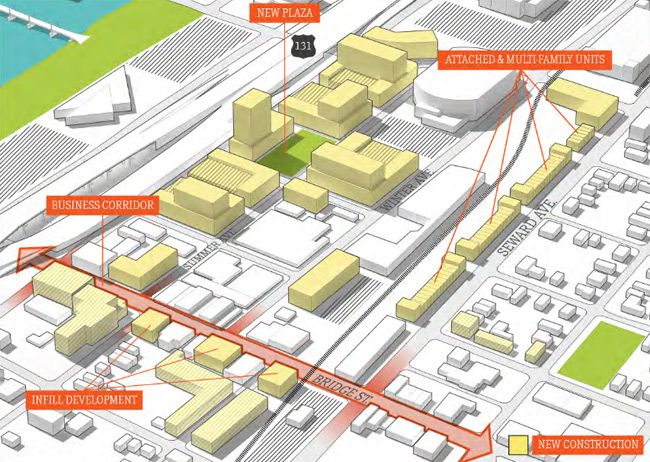

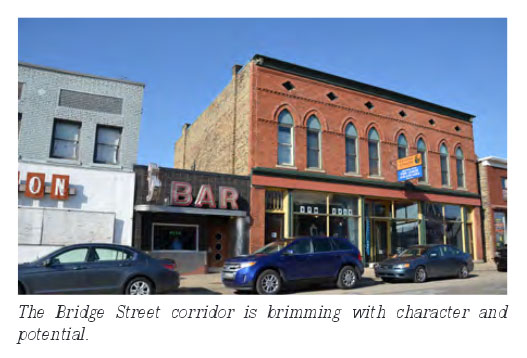

Typical of GR Forward’s approach and vision is its discussion of the Westside. The plan advocates continued construction along and near the Bridge Street corridor, including the building of 4-and-5 story buildings along Bridge and Stocking. They would be a mix of housing and commercial developments. Bridge Street—despite being home to many existing homes and businesses—is presented as prime turf to be colonized by new investments. Already in the neighborhood new housing is being built, all of which features high rents (for example, Rockford Construction’s 600 Douglas and Fulton Place projects) inaccessible to those who traditionally lived in the neighborhood. None of the proposed projects for the neighborhood include affordable housing, and the tepid suggestions for incentives GR Forward suggests won’t do anything to change that. Similarly, most neighborhood business development has been “upscale” stores (the hip and misspelled Denym) and restaurants (Black Heron). These are in many ways typical of commercial development as a whole in gentrifying neighborhoods—it’s designed to meet the demands and interests of a new class of residents.

If what is happening on the Westside is being celebrated by GR Forward, it’s cause for concern as a whole. The transformation of the Westside has been the exact opposite of inclusive and diverse. The Fulton Place development—which is held up by GR Forward as an example of affordable student housing—rents for $800 per bedroom and involved the demolition of existing homes. If this is a template, we should be very concerned when the plan advocates for increased housing for students and young professionals on the Westside and south down Division Avenue. It’s worth noting that the plan advocates for a housing mix in downtown Grand Rapids that is 30% affordable, down from 35% at present. Furthermore, even this call is very limited as seen in the excited discussion about micro-lofts (apartments under 475 square feet) to address the issue of affordable housing. That might be fine for young singles or “empty-nesters”, but isn’t a solution for families who can’t afford high rents elsewhere in downtown.

On the question of public space, the final version of GR Forward continues to call for the total commercialization of downtown. Public space, culture, nature, parks, and people are all seen as “assets” which can be commodified and/or otherwise used to generate economic activity. There’s no real talk about non-commercial space. Instead, parks and the river would be “activated” with a series of facilitated activities designed to cater to tourists and those with money to spend in downtown. Downtown will become a giant amusement park with skate parks, festivals, whitewater rafting, swimming, ice skating, public art, and a host of other activities to take in before or after visiting the hot new restaurant or brew pub du jour. As is typical of GR Forward’s discussion, this assumes that spaces aren’t already used, whether it is a commercial street or a park. For example, homeless people often spend their days in the parks, yet a park such as Heartside Park is seen by GR Forward as needing to be “activated” because it doesn’t have the right type of activity.

This illuminates a major tension in the GR Forward plan between activities that are deemed “good” uses of space and those that aren’t. Drinking by low- and no- income people in Heartside Park is seen as an undesirable activity that needs to be “rooted out”, but drinking craft beer at Movies in the Park is seen as a model behavior. At the same time the plan speaks of creating a welcoming downtown, this tension manifests itself in repeated advocacy of improved lighting, the expansion of the Downtown Ambassadors program, illuminated storefronts, redesigned parks, etc, all of which are designed to police a certain type of street life and activity while inviting in a different set of activities. In the downtown envisioned by GR Forward it is fine to walk drunk from bar to bar while sampling the latest in foodie trends, but to inhabit the street while intoxicated because you have nowhere else to go, means that your presence will addressed in terms of how it relates to people’s “perceptions of safety.” The Downtown Ambassadors—identified as a success and something that should be expanded by GR Forward—probably will not be offering to refer tipsy distillery patrons to services to deal with their potential alcoholism, yet they will not hesitate to refer those whom they deem to be homeless and/or “at-risk”.

GR Forward builds on the reality that downtown Grand Rapids has changed dramatically over the past decade. Those who support both the GR Forward plan and the general trajectory of these changes see this in a positive light. The frequent announcements of new housing, new businesses, and other initiatives lend themselves to the idea that there is an unstoppable forward momentum. Intertwined with this idea is the notion that the city is becoming increasingly progressive and/or otherwise changing for the better. It coincides with the concept of infinite growth in capitalism, that there is always something to be exploited, always an asset to be maximized, and a profit to be made. It goes by different names: entrepreneurship, capitalism, colonialism, but it has always meant looking at the world through an economic lens where everything—from swimming in the river, to street musicians, and diversity—is a potential means to generate more economic activity.

Everyone and everything is a potential niche to market or market to. And as for those who don’t fit into this vision? At best they might be the subject of a token mention in a preamble, but their experience is quickly buried under the forward march of progress. To raise concerns, to register objections, or otherwise critique the existing trajectory is an anachronism when everything is moving forward and everything is progressive. It’s an ahistorical triumph where the past no longer matters and legacies of exploitation can be wished away. At the same time, the tide GR Forward represents washes across the landscape, leaving in its wake a city transformed into an adventure playground built on a landscape that has been thoroughly cleansed, sanitized, and monetized.