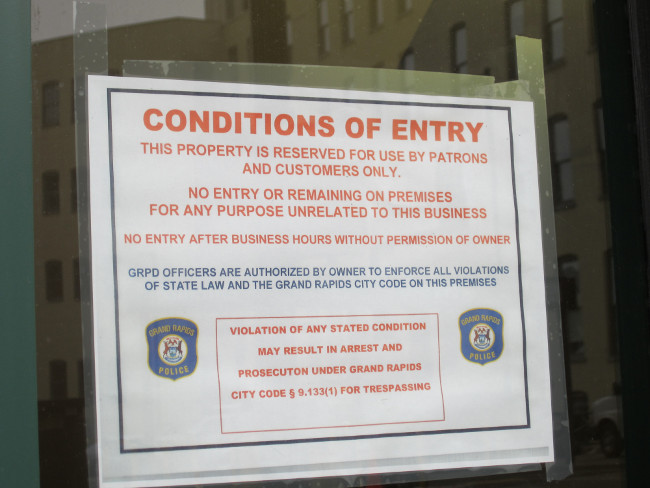

In the urban centers of modern cities, space is intentionally designed. While it might seem haphazard, most things are ordered and structured in a very particular way to facilitate commerce and the circulation of goods and capital throughout the city. Similarly, anything that disrupts—or could potentially disrupt—this flow is an obstacle that must be removed. In the harsh reality of capitalism, these “obstacles” are often people.

People who are not generating wealth, those who are taking space for non-commercial purposes, and those

who in some other way prevent (or might prevent) the conduction of business are obstacles that must be removed. Among the most discussed obstacles are graffiti artists, skaters, youth, and homeless people. Homeless people especially are the target of practices that seek to design them out of urban spaces, as well legal policies that often criminalize their very existence.

There’s a long history of using architectural design to eliminate “undesirable” uses in urban spaces. It goes by different names and has slightly different emphases depending on the exact form it takes: “hostile architecture,” “disciplinary architecture,” “defensive architecture,” or “crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED)” No matter what term is used, it describes a set of practices where urban space is designed in a way to prohibit certain behaviors. The structuring and ordering of space is used to eliminate the need for certain forms of policing: if the behavior is not possible in the first place, policing it becomes unnecessary.

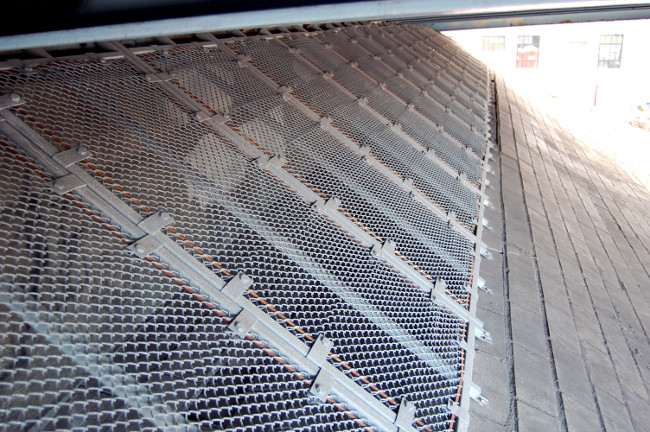

While perhaps not as visible as the “anti-homeless spikes” in London last year that generated considerable criticism, Grand Rapids features a number of examples of “hostile architecture,” the most notable of which is the fence used to prevent homeless people from sleeping under the Wealthy Street overpass near the Downtown Market. In many ways, it’s a perfect example of how architecture is used to signal who is valued in society.

Here are some other examples found around downtown:

“Removing or altering street furniture. Dismantling park benches and the like, or installing spikes and other devices to discourage sitting or lying on flat, raised surfaces, can make places less attractive for idle transients. But this will affect the street homeless and the legitimate user of public space equally, as each will be denied a place to sit and rest. Better approaches involve encouraging property owners to modify surfaces in fairly benign ways or construct them so they do not promote long-term sitting. Examples include central armrests on benches, slanted surfaces at the bases of walls, prickly vegetation in planter boxes, and narrow or pointed treatments on tops of fences and ledges. However, some observers of public spaces argue that the way to lessen the impact of loitering homeless people is to construct even more desirable sitting environments to attract more legitimate users, thus decreasing the ratio of homeless to legitimate users.” – Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

“Poverty exists as a parallel, but separate, reality. City planners work very hard to keep it outside our field of vision. It is too miserable, too dispiriting, too painful to look at someone defecating in a park or sleeping in a doorway and think of him as “someone’s son”. It is easier to see him and ask only the unfathomably self-centred question: “How does his homelessness affect me?” So we cooperate with urban design and work very hard at not seeing, because we do not want to see. We tacitly agree to this apartheid.” – Alex Andreou