When the police officer Darren Wilson murdered Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, it was not a reflection of a broken system, but was instead a particularly visible example of the state violence and racism that is at the core of U.S. society.

In the months since, there has been a lot of talk about the police. Unfortunately, much of it has focused on so-called “police misconduct”—as if the police are doing something outside of their mandated role. In fact, the police are doing just fine as an institution designed to protect property and those in power. Over the years they’ve developed more sophisticated means of doing this—new technologies (surveillance, weapons, etc) and new approaches (“community policing”)—but the underlying purpose remains unchanged.

Despite many people’s wishes, we can’t just reform away the problems of police violence—it must be understood as essential to the function of police. And as such, body cameras, more cops of color, and more sensitivity training aren’t going to change their functioning.

In Grand Rapids, we’ve seen the post-Ferguson discussion dominated by these conversations. Almost immediately after it was announced that Darren Wilson would not be charged for the murder of Michael Brown, a push was made to get the Grand Rapids Police Department (GRPD) to use body cameras. While there has been some discussion of how police actually operate on the ground in Grand Rapids, it has largely been with the assumption that police are generally good and that there are a few simple tweaks that can be made to “improve relations” with the community. And while there may be instances of racism and violence on behalf of the GRPD, those are largely seen as correctable rather than inherent in the way police and policing are designed.

The History and Origins of the Police

“The overseer rode around the plantation

The officer is off patrolling all the nation …

My grandfather had to deal with the cops

My great-grandfather dealt with the cops

My GREAT grandfather had to deal with the cops

And then my great, great, great, great… when it’s gonna stop?! ”

– KRS-ONE, “Sound of Da Police”

Unlike KRS-One, police chiefs and scholars of police studies proudly trace the origins of their institution to the evolution of a more “civilized” society as cities and industry grew. This is certainly accurate, but it isn’t a heritage to be proud of. It’s well documented that the modern police were invented over the course of a few decades in the mid-19th century, during a time when growing mercantile power was threatened by collective action: strikes, riots, and insurrections by laborers and slaves. The police didn’t come into being in response to some sudden outbreak of interpersonal crime, but in rather in response to public dissidence and disorder, and the ability of increasingly wealthy merchants and increasingly powerful local governments to reward others for protecting their interests.

Police departments in the Southern U.S. can trace their lineage to the slave patrols… Even in the North, the informal system of constables… performed racial policing.

This is as true in Grand Rapids as anywhere else, with the Grand Rapids Police Department being established in 1871. Here, as elsewhere, the police department was organized to provide a state-run security force to replace the private constables that had previously been hired by merchants to protect their businesses and property. Reflecting this origin, most of the early police chiefs in Grand Rapids came from military or business backgrounds.

There were methods of supervision and control prior to this development, of course, and the modern police grew out of these threatening mechanisms. Police departments in the Southern U.S. can trace their lineage to the slave patrols – armed white volunteer forces that patrolled the countryside intimidating and brutalizing slaves into submission. Even in the North, the informal system of constables that provided “night watch” to settlements and cities performed racial policing – in colonial times, defending occupied territory from displaced Indigenous people, and later, harassing and intimidating Black people who dared to exist in public spaces.

In this light, it’s easy to understand the historical relationship between policing and white supremacy. The idea of a “white race” was an invention aimed at promoting cross-class solidarity between poor and wealthy white people, based on the idea that skin color was a unifying factor. In exchange for ignoring the differences in class, white men were awarded privileges (ability to own property, right to vote, higher position in the social hierarchy, etc.) denied to the enslaved and free African populations. This white supremacist system was designed in response to slave rebellions and indigenous resistance and ensured stability by keeping poor whites from pursuing alliances with black and indigenous peoples. Despite its historical origins, white supremacy did not go away after slavery’s legal abolition. The police play a critical role in maintaining white supremacy from the Jim Crow laws enforced by police in the post-Reconstruction South to the racially targeted policing of today.

And so the historical origins and purpose of the police are clear – to protect and serve, as they say! But only to protect property and trade, and serve those who own and conduct it – while maintaining a system of white supremacy.

The Police Today

In modern times, police are on the front line of a system of criminalization and punishment that targets people of color and low-income people. The U.S. prison system is the largest in the world and over two million people are in prison. It’s larger than at any point in history — 1 in 99 adults are in prison, and 1 in 31 are under some kind of correctional control. In many cases, prisoners perform involuntary forms of labor for the benefit of private corporations. Of course, the overwhelming majority of those ensnared are people of color.

The police maintain the day-to-day workings of this system. Study after study documents the disproportionate targeting of people of color. This isn’t just on the national level, as if somehow good old Grand Rapids is immune from this type of racism. Here, as everywhere, the Grand Rapids Police Department maintains a white supremacist power structure. For many folks who aren’t white, this is painfully obvious in the day-to-day harassment experienced and the knowledge that whenever they step out their doors they are a target.

Grand Rapids has a long history of racist policing…

Grand Rapids hasn’t made the headlines with any great moments of tumult or unrest lately, but it consistently ranks as one of the most segregated housing markets in the nation, and the city’s arrest rates of Black people double those of Ferguson, Missouri. A recent study found that for every 1,000 Grand Rapids residents, 206 black people are arrested compared to 35 non-black people – a 1 to 6 ratio. In contrast, Ferguson has a 1 to 2.6 ratio. It is common practice for the GRPD to take photographs and thumb prints from individuals they come into contact with who do not otherwise have official identification, and as it always is with policing, it is people of color who are most often subjected to this. Grand Rapids has a long history of racist policing: the “Special Investigations Unit” in the 1920s and 1930s tasked with policing and managing the black population, the use of “no good account” charges until the 1960s to keep people out of certain neighborhoods, the GRPD’s consistent use of “hindering & opposing” charges to target black residents, or a 2004 study showing that people of color were more likely to be stopped while driving.

Over the years, police in urban areas have adopted new theories of policing, where cops target petty crime and individual disorderliness in hopes of displacing or preventing more serious crime. These theories, such as “broken windows,” claim that by aggressively clamping down on small crimes it will prevent a larger climate of lawlessness. In practice, this saturate poorer neighborhoods with police, and disproportionately targets homeless people and people of color, while police and their defenders can still use the excuse that they’re focusing on behavior, not race. At the same time, prison populations grow as more people are arrested and incarcerated.

Much of this has been under the guise of “community policing.” Participating in relations with community organizations, businesses, schools, and homeowners, the police not only get the PR of looking like they’re acting in harmony with the communities they prowl, they also are able to more closely monitor potentially unruly populations. Community policing generally emphasizes relationships with those who already have power in society, reflecting the underlying design of policing.

As “community policing” has grown in prominence, there has also been an increase in the militarization of the police. Since at least the early 1990s, the tendency of the state has been toward more police and more policing — federal grants, more cops, bigger budgets, and heavier weaponry. A federal program started in 1990 dispersed military surplus equipment to state cops specifically for use in the “War on Drugs.” The origins of the “War on Drugs” are complex, but it has often served as a convenient excuse for the continued targeting of people on the basis of race, as seen in the well-documented sentencing disparities that exist in enforcement. Police also haven’t limited the use of these weapons to drug-related activities and in many cases police departments use military equipment in the execution of search warrants, crowd-control situations, and other day-to-day activities (for example, the increasing numbers of police departments who have their officers wearing military fatigues). Transfers of military equipment have increased in the past few years. Michigan police have received $43 million worth of military equipment since 2006, including everything from armored vehicles to grenade launchers.

…modern policing has also involved the expansion of so-called “softer” forms of policing… private security firms, the expansion of the surveillance state, and variations of the aforementioned “broken windows” policing.

Along with the PR-friendly face of “community policing” and the harsher reality of militarized police departments, modern policing has also involved the expansion of so-called “softer” forms of policing. This is seen in the increased reliance on private security firms, the expansion of the surveillance state, and variations of the aforementioned “broken windows” policing. In Grand Rapids, the “Downtown Ambassadors” program fuses many of these. The “Safety Ambassadors” operate under the guise of making the city more welcoming to tourists, but more importantly they aid in the political project of “cleaning up” downtown – moving homeless people out of visible areas, documenting petty crime, cleaning up graffiti, and generally making the streets palatable and inviting for the current transformation of downtown. A critical part of their job is keeping extensive records on the people they come into contact with and funneling information to the GRPD. This all relates back to the founding of the modern police system, which was designed to protect those with money and power.

You Can’t Reform a Broken System

In Ferguson, people responded in a way that made immediate sense to them: they targeted the places and institutions that they saw as being representative of the police violence that killed Michael Brown and that targets them on a daily basis. However, as the response to Ferguson took shape on a national level, the conversation shifted into the realm of reform. It’s notable how in most of these conversations, the word “solution” is rarely used. Instead, many of the same words pop up over and over: “reforming,” “curbing,” and “mediating.” Even the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), an organization devoted to legal reform and good law enforcement, admits that police abuse “has a long history, and seems to defy all attempts at eradication.”

police abuse “has a long history, and seems to defy all attempts at eradication.”

As it turns out, the ACLU is on to something. No amount of reform is going to be able to change how the police function. Instead, all reform can do is limit dissent and restore faith in the police—which is the basic goal of reform no matter in which context it is used. That’s why we see the Grand Rapids Community and Police Relations Committee being so willing to make a few token changes. In the interest of the police and those who benefit from them, it makes strategic sense to offer a few relatively inconsequential reforms in order to avoid a larger rebellion. Former City Commissioner Robert Dean really did say it best, “it’s really a matter of trust. We’re fighting perceptions.” Those in power—and those who ally themselves with power—want to ensure “an environment that ensures civility and respect between the community and the Police Department.” And that must be done as quickly as possible. The police are not concerned with state violence as violence is an everyday part of policing—it is the appearance of order that is absolutely essential.

More Eyes on the Street, More Sellouts in Power

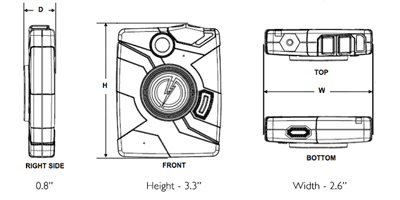

Almost immediately after it was announced that Darren Wilson would not be indicted, the conversation over police abuse in Grand Rapids shifted to a discussion of body cameras. A local organization, LINC Community Revitalization, proposed that the GRPD require its officers to wear body cameras and the media and the City government quickly made this the main point of discussion. There was a predictable public back-and-forth between the police, community activists, and the government about it, but it had the practical effect of reducing any conversation about the nature of police and policing down to a simple discussion: should cops wear cameras? Aside from a few comments at various public hearings, the day-to-day actions of the police in Grand Rapids were ignored.

There are plenty of problems with body cameras. There is little evidence that they will make police less likely to use brutality. We must remember that many instances including the beating of Rodney King in 1992, to the killing of Oscar Grant in 2009, and the recent murder of Eric Garner were caught on camera and all of those cops walked. Police are filmed brutalizing people all the time and they never see disciplinary action besides the occasional temporary suspension (read: paid vacation). Since the recordings are in the hands of the state itself, we will likely continue to see these cameras “malfunction” during exceptionally brutal acts. There is an oft-cited study claiming that body cameras cut down on use of force. This actually was conducted by the chief of a small police department that was under threat of being dissolved if they didn’t cut down on their use of force. Other studies reach similar conclusions, cameras more often help the cops than those brutalized by police. Like any gang, police protect each other, and departments will resist turning over information that will compromise one of their own. It’s no surprise that the makers of body cameras routinely advertise them as a ways to help protect police—not those who they target. A prominent manufacturer of body cameras, VIEVU, uses the slogan “Made By Cops For Cops. Prove Your Truth.”

The state regularly uses “crisis” situations to expand its power, so it’s important to remember that more cameras in the hands of cops means more power in their hands.

From the perspective of the state, the logic for body cameras is sound. Body cameras expand the systems of surveillance that exist in the modern world. Body cameras will join the surveillance cameras already in place in Grand Rapids (which the GRPD recently gained real-time access to) and license plate scanners that record the movements of vehicles in the city. As shown in the recent debate over NSA surveillance, people tend to be skeptical of increased surveillance and some understand that more surveillance means less options. However, packaging body cameras as a way to increase “accountability” makes it the surveillance seem more palatable. The state regularly uses “crisis” situations to expand its power, so it’s important to remember that more cameras in the hands of cops means more power in their hands. It’s the same when the City discusses “community policing” as a way of expanding the total number of officers. Even if the job description changes, the power of the police increases.

It makes sense for the City of Grand Rapids to willingly adopt body cameras. It’s an easy way to give the appearance of making a change, even though it will just expand police power. Buried deep in the City’s recommendations is the fact that the City’s collective bargaining agreement with the police union includes a provision stating that new technology cannot be used for disciplinary purposes during the first year of its use.

As with body cameras, we should be skeptical of calls to increase the hiring of more cops of color. This is a perfectly palatable reform for those in power, which is why the city is so willing to pursue it. The consequence of efforts such as an NAACP scholarship for people of color to enroll in the police academy or new hiring practices targeting people of color, means more praise for the police. In other cases, recommendations such as an increased visibility of the GRPD in Grand Rapids’ schools simply means more policing of already targeted populations. All of this presumes that the problem is either inequitable representation or individual white racist officers – when the problem is a system that rewards officers of all colors for protecting power and its interests. The police as an institution serve the white supremacist power structure and individual cops are unable to challenge or change it, regardless of the color of their skin. We should celebrate those who refuse to be cops. In the case of black youth, they likely understand how the police function, and as such, why would they want to join?

In the recommendations made by the Community and Police Relations Committee, nearly two pages out of a seven-page document were spent dispelling the need for a Civilian Police Appeals Board with subpoena-power. The City and GRPD are steadfast in their opposition to this, which gets to the core of the problem of reform. When it comes time to implement changes that might have actual consequences, the reforms are suddenly can’t be made. The City plans to launch a public education campaign to increase awareness about the Board, even as acknowledges its limitations. The Appeals Boards is entirely review-based and has no power to interview witnesses or otherwise investigate allegations, and most certainly “has no power to impose discipline.” All it can do is act on the words of the GRPD’s Internal Affairs Unit, and there’s every reason to be skeptical of police investigating themselves. Time and time again, police line-up to protect their own. We see glimpses of this in the police union’s opposition the City’s approved reforms and as well as Chief Rahinsky’s admission that he knows of no Grand Rapids cops have been removed from their job for an instance of abuse in “recent memory.

If not Reform, then What?

Despite their many flaws, police are still seen as necessary. Those who benefit most from the police would hate to see them abolished or destroyed, they prefer to see them managed and reformed. In this way, the well-meaning reformers collude with those with whom police are designed to protect. Both assume that the problem is on the surface, rather than at the core of the institution. The problem is assumed to be one of individual misconduct and a lack of oversight or training. For those of us caught in between these positions, police are often seen as a necessary evil – something haunting that we live with over our shoulder, but without which we’re not sure what the world would look like. Police are often seen as our only option, only they can provide the illusion of safety and order in a highly stratified society.

Rather than talking about body cameras, we need to ask deeper questions. To whom are the police necessary? What role do they really serve?

The truth is, we don’t need nicer cops. We don’t need cops with more community-sensitivity training. We need fewer cops. We need alternative methods for keeping each other safe and holding each other accountable. In the end, maybe we don’t need cops at all.

In order to get there, we’ll need imagination and vision. But we can begin that process by understanding that modern policing came out of a specific need to protect property and commerce and to enforce racial and class divides. The cops have always functioned this way – and they always will.