When speaking of development or gentrification in Grand Rapids, a constant refrain heard from city leaders, developers, and even many opponents is the need for more “community involvement” or “community engagement.” Development is presented as if it is a dialog or a process in which we are all on equal footing, rather than something done by those with considerable capital and political power. The appeals for participation are repeated over and over: the city and developers allegedly want to hear from the “community”, while always looking for more ways to get people involved.

However, what is actually being encouraged is a very specific and narrow form of “involvement” that centers around the process of attending city meetings, meetings with developers, and other such similar events. It’s presented as a type of civic duty akin to voting – if you don’t do it, you don’t have a right to complain. A sort of hyper-local version of “America, Love It or Leave It.” Often when these conversations happen, they involve a considerable amount of blame being placed on those who are critical. The assumption is always that they have chosen “not to be involved” and that because they allegedly aren’t participating their voices aren’t being heard, and therefore, their concerns aren’t being addressed. It’s a charge that has been leveled at us repeatedly over the past year: that if we participated in the allegedly “important meetings” that are happening, “our voice would be heard”. Of course, as we have written before – we have attended these meetings, eaten the free pizza, rolled our eyes with our neighbors, and engaged in the various activities dreamed up by consultants who are paid to gather “input” (see for example, GR Forward) – but it’s an issue that is much bigger than us. The people affected by these projects are by and large absent from the decision-making process. While the City and developers tend to blame residents – with the most recent example being City of Grand Rapids Planning Department Director Suzanne Schulz stating that neighbors need to get more involved and be more clear in their articulation of “what they want” at a recent lecture on gentrification at Grand Valley State University – the onus shouldn’t be placed on residents, rather, the problem lies with the City and how they define participation.

The Planning Commission

In terms of gentrification and development, one of the most important decision-making bodies in Grand Rapids is the Planning Commission. It’s a nine member body tasked with “preparing and adopting a plan for the physical development of the city.” In practice, this means reviewing new building projects, changes to zoning ordinances, etc. It’s the governmental body that approves, denies, or amends projects. The nine members are supposed to “represent different professions and occupations and provide a wide range of citizen interests in land development issues.” In practice, many of the members are connected to real estate and/or other development interests. They are appointed by the Mayor of Grand Rapids for three year terms, with a maximum of three terms or nine years.

If a major project – such as a market-rate housing development – is proposed in a neighborhood, it is the Planning Commission that hears resident concerns. They will schedule a “public hearing” – a block of time at their regularly scheduled meeting – where they will take comment from the public on the proposal. When a hearing is scheduled, residents and property owners living within 300 feet of a proposed development will receive notice by postcard of the hearing, while a printed notice is published in The Grand Rapids Press 15 days prior. Comment can also be submitted via letter.

Beyond this, developers are encouraged to schedule a “neighborhood meeting” about a project before presenting their request before the Planning Commission. According to Grand Rapids’ Zoning Ordinance, the meeting is designed to do the following:

“The purpose of a neighborhood meeting is to educate occupants and owners of nearby properties about the proposed development application, receive comments and address concerns about the development proposal; and resolve conflicts and outstanding issues, where possible. The meeting is intended to result in an application that is responsive to neighborhood concerns and to expedite and lessen the expense of the review process by avoiding needless delays, appeals, remands or denials.”

The ordinance further specifies that the meeting shall be held in a “neutral location after 5 p.m. on a weekday.” Developers are also expected to circulate a sign-in sheet and provide the information to the Planning Commission at a later date.

Democracy in Action

In the idealized world of citizen democracy, then, we should all be expected to exercise our rights as citizens to participate in the democratic process by attending these meetings. However, there are many barriers that keep even the most interested from participating. Among these is the rhetoric of “citizenship” – it ignores that some of the most vulnerable – and occasionally most affected – are not “citizens”. They might be the workers who pay cash for rent, who lack the ability to challenge slumlord landlords in court, or who will wash the dishes at the hip new restaurants. This is merely one of many ways in which the process is one of exclusion, not inclusion.

If one wants to attend a Planning Commission meeting, they happen on the second Thursday of each month at 1:00pm at the City’s Development Center, located at 1120 Monroe Avenue NW. As needed, additional meetings are scheduled on the second Thursday. Meetings vary in length, but they generally last for several hours. For example, the March 10, 2016 meeting adjourned at 4:20pm. This means that if the topic you came to speak about is late in the agenda and you are one of those who have steady 9-to-5 employment in the current precarious economy, you will likely have to take off an entire afternoon from work or find childcare if you are parent. Additionally, to understand exactly what is being discussed, you will generally want to read through the “Agenda Packet” which is often well over 100 pages long, full of charts, applications, graphics, and other such things written in inaccessible language. Clearly, this is not a process that screams that participation is valued.

Assuming that you can get the time off from work, find childcare, or have several hours on a Thursday with nothing better to do, the meeting itself is not a very welcoming atmosphere. It’s kind of like walking into a party where you don’t know anyone and everyone else is already friends. There are various city officials, occasionally cops, the Planning Commissioners, and developers all hobnobbing and slapping each other on the back and shaking hands. If you are lucky, there might be a few other people you know – especially true if something is a particularly contentious issue – but for the most part, it’s a lonely affair. Most of the people are in suits or other professional attire. There are sometimes contractors in attendance, but for the most part, this is a professional crowd and professional norms dictate expected behavior. Those who are on the Commission, attend the meetings, and speak tend to be professionals (developers, architects, investors, etc). The majority of those in attendance have college degrees, often from graduate or professional programs. There are typically very few working-class or low income people in attendance, even though many of things being discussed will inevitably affect them. We shouldn’t blame them for their absence, but rather should ask what it is about the process that excludes them. If you walk into the room, complete with snacks and drinks for the Commissioners, it’s hard to miss why people might feel excluded – the professionalism and concomitant whiteness is unavoidable.

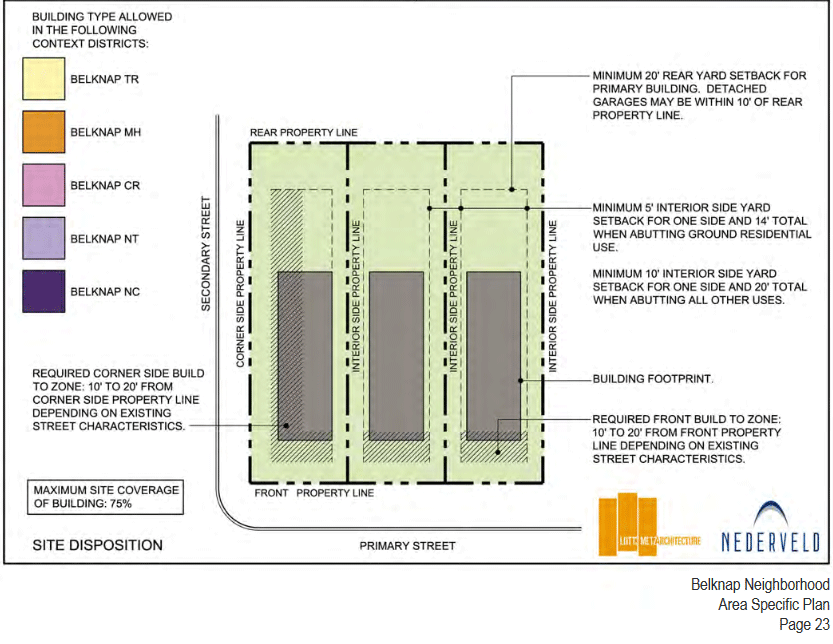

If you decide to speak at the meeting (which again supposes you were one of the few living within 300 feet of a project and/or that still read The Grand Rapids Press’ print edition to find out about the meeting), it’s essential to understand that what happens at a Planning Commission meeting isn’t a simple conversation, but rather it’s a convoluted process that happens through the use of highly specialized and professionalized language. Prepare to hear a lot of acronyms (TN-LDR, TN-TCC, SD-IT, ASP, etc, etc), specialized terms (density, setbacks, special land use, etc), and processes. There will typically be a lot of discussion about building heights, building materials, parking spaces, signs, etc. For the uninitiated, it’s hard to make sense of it all and nobody is there to make it accessible or understandable. It is a process that works best for those in power – the City, the developers – if there isn’t much participation.

Comment is sought primarily in relation to very specific points, i.e. should a development of 5 stories be allowed in a TN-LDR zone despite a limit to buildings of 3.5 stories (a hypothetical example). While you can get up and theoretically say whatever you want, the Planning Commission tends to value the points that relate most specifically to City Code or Zoning regulations, which few are conversant in. For example, a debate might center around whether or not a particular project is “consistent with the Area Specific Plan (ASP)” which of course assumes both a familiarity with the ASP, a knowledge of what those are, and how to interpret them. Not surprisingly, there often isn’t public comment. To cite the March 10, 2016 meeting again, there was only one public comment on one agenda item. Commissioners will often argue against issues raised in public comment, saying that despite the concern, it’s unfounded – again, it’s not something that makes you particularly empowered. Even in situations where there is comment and residents come out in opposition to a particular project, it isn’t uncommon for Planning Commissioners to vote unanimously in favor of a project.

Neighborhood Meetings

The neighborhood meetings that are encouraged by the Planning Commission – albeit specifically not required (after all, Section 5.12.04 says that “Failure to hold a neighborhood meeting shall not stop or delay the review process; however, such an omission may result in the tabling of a request.”) – tend to follow a similar pattern where the same power dynamics and imbalances come into play. Meetings aren’t advertised well as there is no specific process outlined by the city for how developers should do that. Consequently, meetings are usually sparsely attended, with a representative from a particular development company often presenting to a neighborhood association about “what is coming”. These aren’t really conversations – the project is typically already decided – and the whole affair seems more like an exercise in checking off boxes rather than a dialog based on respect. Often, there’s food – as if a developer throwing down some cash for some food from a local restaurant is going to win over the “hearts and minds” of the people. What inevitably happens is that there is some type of push back from neighbors and that the developer – one of only a few in the room in a suit – talks down to residents and asserts the clichéd mantra that “change is inevitable”. Even when opposition is quite strong, the “sign-in sheet” – circulated by developers to show that they “consulted with the neighborhood” – will be presented to the Planning Commission as proof of their “community engagement”. Often the sheet will simply be thrown in the Planning Commission’s “AgendaPacket,” with little comment about the contents of the meeting. Simply because the developer presented the plans, this is counted as community engagement—regardless of reaction to it.

ASP, CID, BID, DDA, and the ABCs of Exclusion

Other venues for participation touted by the City are equally disempowering. A favorite of Planning Director Suzanne Schulz is the Area Specific Plan (ASP), an often multi-year planning process that functions as a localized master plan for a specific area of the city. Just as the City of Grand Rapids as a whole has a master plan, an Area Specific Plan attempts to outline and facilitate development of a smaller area. However, there are the usual problems associated with the City’s planning process in that they tend to be dominated by developers and business interests. For example, the Westside ASP Steering Committee features many of the same politicians and developers responsible for the gentrification of the Westside. The same is true of the Belknap ASP. It’s a lengthy and involved process which demands considerable work on behalf of those convening them. While they may give some guidance to developers – there’s a convincing case to be made that they aren’t particularly helpful in addressing resident concerns. In the case of the “U to the Zoo” ASP covering West Fulton and Seward streets on the Westside, the ASP has been approached as an obstacle by developers – something that is meant to be stretched and interpreted, rather than a specific rule. In this case, projects such as an apartment project on the corner of Lake Michigan Drive and Seward or the construction of Rylee’s Ace Hardware on West Fulton were both approved despite being contrary to the ASP for the area. Even after engaging in a multi-year process that the City touts as a way to be responsive to resident input, by ignoring it they send the message that resident input isn’t valued.

Engaging with the City Commission – another common venue for resident public comment – is also a relatively meaningless gesture. While meetings are held in the evenings on every other Tuesday at 7:00pm and are even geographically dispersed to encourage more participation, it isn’t clear that participation is any more valued. The meetings tend to follow similar dynamics to what has been outlined above, albeit with a more friendly face. The Commissioners give off a more understanding and accessible air and they are at least electable and not appointed. However, much of the work is done behind the scenes or at meetings that are significantly less accessible – for example the 9:30am “Committee of the Whole” meetings – where anybody who follows the City Commission will tell you “the real work” gets done. It gives the 7:00pm meetings a sense of performance, where most decisions have already been made. In some ways, they are characterized by theatrics with occasional contentious debates about neighborhood developments, policing, or as a site of protest.

In the large bureaucracy of the City there are other boards and entities which have considerable influence over the City and that claim to be open to input, but really aren’t. A prime example is the Downtown Development Authority (DDA) which essentially guides the development of downtown Grand Rapids. It’s tasked with the mission of eliminating “…property deterioration, to increase property tax valuation where possible in the City’s business district, to eliminate the causes of deterioration, and to promote economic growth” – in other words – it’s a major facilitator of the gentrification of Grand Rapids’ downtown core. It meets at 8:00am on the second Wednesday of each month – and all previous discussion about barriers to participation stand. There’s a host of related committees (Alliance for Livability, Alliance for Vibrancy, DGRI Board of Advisors, etc) and figuring out where to bring a specific concern is difficult. While theoretically open to the public, it’s rare that anyone participates in these meetings besides their members. The same can be said of Corridor Improvement Districts (CID) and Business Improvement Districts (BID), which both use a variety of financing and tax capture avenues to facilitate improvements in public infrastructure. Most often, these are things like planters, bike racks, public art, etc. They tend to be the kind of thing that can “improve” a neighborhood’s physical appearance, but at the same time, can be used as means of facilitating gentrification. For example, they may try to “brand” a neighborhood as a new hip destination, as has been done on the Westside. On a CID, there is a spot for one resident to serve and while public comment is allowed, there rarely is any given.

Looking Deeper, Broadening Understanding

Participation shouldn’t be restricted to participating in formal structures outlined by the government. As discussed above, these are most often structured in a way that does more to exclude participation than invite it. Whether they are meetings scheduled during the weekday, hearings held as a rubber stamp, or conversations dominated by large power imbalances, it’s clear that what passes as “community engagement” often has significant barriers to participation. It’s characterized by a professionalized and educated discourse – which in a society characterized by countless divisions of which those by race and class are some of the prominent – tends towards a discourse which is very middle-class and white, thereby excluding large portions of the population.

This isn’t a call for more accessible meetings, as if the problems could be solved if we changed the words we used, calculated the accurate formula for a “truly diverse board”, or scheduled meetings in the evenings, but rather for a deeper understanding of engagement and participation. In the case of gentrification, we need to understand that participation is going to mean a lot of different things to different people, some of which may be outside of the traditional structures of civic engagement. It could mean small informal gatherings with neighbors, conversations amongst religious congregations, blog posts attempting to understand what is happening, conversations among friends, study groups, alternative media, art, or public discussions. As more people lose their homes, are pushed out, or are displaced by rising rents, it may mean other forms of political action. In Grand Rapids, the City has been clearly engaged in a policy of gentrification for the past several years, and we should consequently expect that many people won’t see the value in participating in processes that have facilitated gentrification, especially when these processes exclude so many.

Rather than chastising people, we should be making alliances, forming plans, and figuring out ways to stop the gentrification of Grand Rapids.