In the weeks and months after the August 2014 police murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, the issue of policing in the United States was at the forefront of discussions. For those who experience the physical and psychological brutality of the police, these discussions were not new. Nevertheless, a seemingly endless barrage of politicians and pundits discussed policing, reform, and the possibility for change as if somehow the reality of policing as a white supremacist endeavor had escaped them for all these years. The results were predictable: the debate was shifted towards body cameras, ShotSpotters, community policing, and other solutions that didn’t challenge the underlying system of policing.

This was true in Grand Rapids, where much of the debate around policing centered on the topic of body cameras. Following a protest in response to the decision not to indict Darren Wilson and a community forum, any general criticism of the police was quickly channeled towards calling for body cameras. The call was initiated by the non-profit organization LINC who dubbed the campaign #OperationBodyCamGRMI. It was enthusiastically taken up by the City Commission despite initial objections by both Police Chief David Rahinsky and the Grand Rapids Police Officers Association. Even after the City of Grand Rapids issued a broader set of recommendations for improving relations between Grand Rapids Police Department (GRPD) and city residents, much of the public debate still focused on body cameras. In its place, there was a steady stream of articles on body cameras, giving updates on how they would be paid for, how cops who tested them thought they would work, new policies governing their use, limits of cameras, and what company will be providing the cameras. In effect, what could have been a comprehensive discussion of the nature of policing and racism in Grand Rapids was narrowly contained.

The limiting of this conversation is important as it highlights a way in which the Grand Rapids Police Department and police in general seek to operate in the post-Ferguson world. Police have begun to understand that managing conflict and public perception is a critical aspect of their daily activities. In light of both heightened scrutiny and the reality that police keep killing people, managing perceptions has become essential. The United States Conference of Mayors identified this as one of its core recommendations for improving relations between police departments and the communities they police. Police across the country have undertaken media trainings and are developing sophisticated media strategies that seek to manage events.

In Grand Rapids, the form has varied from the management of crisis to rather crass endeavors that seem almost painfully obvious. An example of the latter is Chief Rahinsky announcing that the GRPD will ask the Michigan State Police to investigate any officer shootings as a public relations move to avoid criticism. In the case of the former, there has been the appointment of a full-time “Public Information Officer”. The appointment was tied directly to the post-Ferguson discussion, with the GRPD claiming that it was another effort at providing police “transparency” for the public.

As a government agency, the Grand Rapids Police Department regularly issues news releases to local news agencies about incidents, investigations, and changes in department staffing. They’ve operated both a website and a Facebook page for years. However, the Public Information Officer demonstrates a new idea of policing that seeks to always cultivate a positive portrayal of police and quickly diffuse any criticism. One way this can happen is by simply increasing the number of relatively benign stories about the GRPD that appear in the media. In the last year, this has included stories about new police dogs, new Segway vehicles for police, media ride-a-longs with officers, police playing baseball with kids and feeding homeless people at a local shelter, and a father-son working relationship. These are obviously all crafted to improve the public perception of the police, largely by humanizing them or doing what Information Officer Terry Dixon said is to challenge the “negative” impression of law enforcement.

In response to Ferguson, there has also been a significant effort to improve the perception of police among youth, who often face the brunt of police aggression. Efforts like the Junior Police Academy are clear in their campaign to change the publics views. In addition, at least part of the body camera discussion was seeded by police which begs the question as to whether or not it was a strategic decision by police to go along with the cameras (especially once the GRPD realized that body cameras will exonerate them and not help residents).

However, the media strategy is about more than just the realm of ideas and portraying police as friendly members of the community, it is also about responding to criticism and neutralizing it. In the public relations world, this might be called “controlling the narrative”, and it is essentially what the Grand Rapids Police Department has been doing after Ferguson. Two high profile examples over the past year demonstrate what this new strategy looks like and both involve the police’s aggressive use of the media to silence criticism.

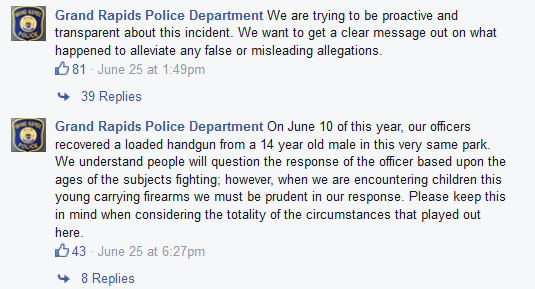

In an incident that happened in Martin Luther King Park on June 24, 2015, a GRPD officer—who was white—used a Taser to allegedly stop a fight happening at the park. A video from a bystander was posted on Facebook which shows the a cop pointing a Taser at 3 unarmed African-American youth ages 12-13. He used the weapon to keep them on the ground for several minutes until multiple cars came to detain the teenagers. As it should, the video prompted intense criticism of the GRPD both in this situation and more generally of their policing of people of color. Likely knowing that this might reveal the day-to-day brutality of policing, the Grand Rapids Police Department’s Information Officer responded aggressively, issuing a news release the next morning saying that the police officer “deployed the Taser properly.” The police also scheduled a media event to answer journalist questions and offered police video to incite them to come. This shaped the narrative by shifting the discussion from questioning police conduct to reporting the police perspective that the incident was justified (see the Mlive and WOOD TV 8 stories on the incident) and diffused what had the potential to become a crisis. Even if the GRPD’s justification seems absurd, it succeeded in controlling the situation and dominating official discourse, moving it away from police conduct and towards “preventing violence”.

A similar incident happened again in September. A party on Giddings Avenue on the Southeast side of Grand Rapids was broken up by police who arrested 9 people and Tased 1. In all, 35 police officers responded to the party. Once again, a video of the police actions was posted on Facebook and quickly spread across people’s social networks, being shared several thousand times. As was the case with the MLK Park incident, people were highly critical of the Grand Rapids Police Department’s actions. In this case, police declined to directly defend their actions pending a complaint via internal affairs, but they still sought to dominate the narrative and generally make excuses for their conduct. The GRPD released a video showing their perspective and made themselves available for comment. Later, they released a staggering 15 hours of video to the media. FOX 17 reported that the police said they released the video to be “as transparent as possible,” but the transparency claim hides the fact that by dominating the media narrative they are seeking to quell criticism.

Defending of police practices is a regular activity of the Information Officer. In response to news that the GRPD wanted to equip all police vehicles with assault rifles, Dixon was there to defend the decision even as the militarization of police has been criticized across the country. The same was true of the expansion of police surveillance cameras, which when pressed with questions about the price, Dixon responded, “Can you put a dollar amount on your safety?” Dixon seemed to welcome recording of police by residents, but at the same time dismissed it because it “only captures one particular narrow point of view.” At times, it’s getting across a core message of policing: that the use of force could be avoided if people simply complied. In some cases, the police must support their own while giving the appearance that they care about others. Rather than dismiss outright a local billboard proclaiming “Blue Lives Matter” or simply endorse it, Dixon replied with the seemingly more diplomatic: “Our law enforcement officers, they matter, but at the same time we also recognize and we know that every citizen that walks here in Grand Rapids, their life matters; every single one.” Perhaps needless to say, the notion that “all lives matter” has been a way of minimizing and diverting the Black Lives Matter movement, while “Blue Lives Matter” has invoked the idea of an imaginary war against police.

In essence, this is what the entire post-Ferguson debate comes down to: putting a friendly face on the Grand Rapids Police Department while avoiding substantive change in practice. The much touted language of “community policing” provides an excellent example of this. As author Brendan McQuade writes:

“In the most general sense, community policing encourages residents to report crimes to the police and calls upon them to resolve disputes. Police are implored to get out of their cars and walk the streets, residents to aid in the hunt for the bad guys. But community policing is never simply a well-intentioned effort to bring the government closer to the people. It enlists residents and community leaders in the work of policing. It informally incorporates residents into the state’s repressive apparatus.”

In other words, while the Grand Rapids favorite “Coffee with a Cop” or partnerships with neighborhood associations might seem innocuous, it is not changing the underlying goal of policing, merely changing how policing happens. Community policing and the use of the media by police departments is part of a broader strategy that takes police in the direction of counter-insurgency. Counter-insurgency can be defined as an approach “characterized by an emphasis on intelligence, security and peace-keeping operations, population control, propaganda, and efforts to gain the trust of the people.” In this approach to law enforcement, the psychological or media-based battle for ideas are as important as physical control. However, the policing cannot happen without both aspects. Approaches such as “Weed and Seed” mix “community” based approaches of “seeding” a neighborhood with social programs while the hard edged “weeding out” of so-called criminal elements. While discussions of militarization of police often look solely at weapons, the emergence of counterinsurgency approaches also bears consideration. Since the 1960s, there has been a continual exchange of information between military and police agencies with community policing and counterinsurgency strategies of the police and military melding into a shared set of tactics, both domestically and internationally.

In other words, while the Grand Rapids favorite “Coffee with a Cop” or partnerships with neighborhood associations might seem innocuous, it is not changing the underlying goal of policing, merely changing how policing happens. Community policing and the use of the media by police departments is part of a broader strategy that takes police in the direction of counter-insurgency. Counter-insurgency can be defined as an approach “characterized by an emphasis on intelligence, security and peace-keeping operations, population control, propaganda, and efforts to gain the trust of the people.” In this approach to law enforcement, the psychological or media-based battle for ideas are as important as physical control. However, the policing cannot happen without both aspects. Approaches such as “Weed and Seed” mix “community” based approaches of “seeding” a neighborhood with social programs while the hard edged “weeding out” of so-called criminal elements. While discussions of militarization of police often look solely at weapons, the emergence of counterinsurgency approaches also bears consideration. Since the 1960s, there has been a continual exchange of information between military and police agencies with community policing and counterinsurgency strategies of the police and military melding into a shared set of tactics, both domestically and internationally.

So when the Grand Rapids Police Department engages the media, partners with organizations, and participates in community forums, it does so not because it has fundamentally changed, but rather because it is adapting to a new reality. It is now necessary to control the narrative, just as they control the streets. The GRPD is all too willing to go in front of a crowd, smile, nod, affirm concerns, pretend to listen, and even engage in a little self-criticism, but it’s all part of a carefully concocted strategy that is designed to control and manage situations and to always put itself in advantageous position.